Choi Wong: Caught In A View, Review by Sharyn Bachelda

Choi Wong: Caught In A View

@ Plaatsmaken, Arnhem, NL

February 2020

By Sharyn Bachleda

Nestled next to an old windmill tower that reads “De Kroon,” lies a brick building, home to Plaatsmaken, a humble maker space for emerging and professional artists. Translated to “make place,” this lovely maker space for visual artists rests in the town of Arnhem, located in central Holland. Plaatsmaken offers silkscreen, etching, relief, and toyobo printing, as well as a digital video studio, digital printing studio, and a traditional photographic darkroom. In the entrance of the work space is also a delightful art gallery with work from local artists.

From January to February 2020, Plaatsmaken exhibited a solo show by Utrecht-based artist Choi Wong, Caught In A View. Traditional black and white gelatine silver photographs and blue cyanotype prints adorned the gallery walls, creating a mesmerizing flow, a feeling of nostalgia, a feeling of connection, isolation, and that puzzling urge to fill in the gaps, or try.

“We see ourselves in these faces, we see people that remind us of someone we know or could know.”

Choi uses found photographs in her work, and for this show, a collection of negatives she acquired at a flea market found their way into the darkroom to be resurrected during a residency with Plaatsmaken. According to Inge of Plaatsmaken, Choi was invited with a project grant from the Mondriaan Fund, a Dutch foundation for visual arts and cultural heritage, one of the biggest funds for the arts in the Netherlands.

Walking down the gallery walls, the work sparks many conversations and thoughts about memory and nostalgia, but also about rearranging, rewriting the narrative to create one that anyone can walk into. There’s something about finding old photographs and imagining their story. We see ourselves in these faces, we see people that remind us of someone we know or could know. Or maybe we just imagine who these characters could be, where they were going, what they were passionate about, etc. Either way, there's this sense of wonder as we peer into these founded histories. The way Choi not only collects these photographs but rearranges them provokes thought about collective memory, collective consciousness that is especially alluring right now.

Discover.

Collect.

Recollect.

Destroy.

Recreate.

Manipulate

Caught In A View, Choi Wong.

Upon walking into the gallery, we see several blue photographic prints on cloth dancing playfully on the wall. The prints are cyanotypes, a 19th century alternative photo process that uses light sensitive chemicals that are painted onto paper or fabric and later exposed with objects or contact negatives in an ultraviolet light source, most generally the sun or sometimes a UV lamp. This printing process can be very finicky as one cannot simply control the weather, especially in Holland. Even using a lamp, the chemicals react to every type of paper and fabric differently. The exposure times range from a few minutes to about an hour depending on the available sunlight. It can be nearly impossible to get the same result twice, which is the beauty of cyanotypes; they are truly one of a kind works of art. Trial, error, and patience are inherent in the development of this work. Upon researching, we learn that Choi used Plaatsmaken's screen printing UV lightbox to expose the prints, a very wise choice with so many cloudy, rainy days here in Holland.

Something engaging about Choi’s approach is the experimentation in the prints. Plenty of artists who work with cyanotypes simply rely on the image, but Choi mixes things up. In some of the fabric pieces, we see a deliberate use of folds becoming prominent obstructions in the composition, creating another voice in the work, maybe even drawing attention to the metaphorical folds of time that have passed since the original photo was taken; the ripples of time, memory, experience, and the ever-changing nuances in perspective that become entwined in the process. We are left to wonder and wander. We see sewn-in patterns that evoke waves, allowing the pieces to take on a sculptural element. No longer bound to the two-dimensional realm, it's almost as if the pieces are reaching out as they get closer to us, as if there's an energy field disrupting the gaze and transforming it into more of a conversation.

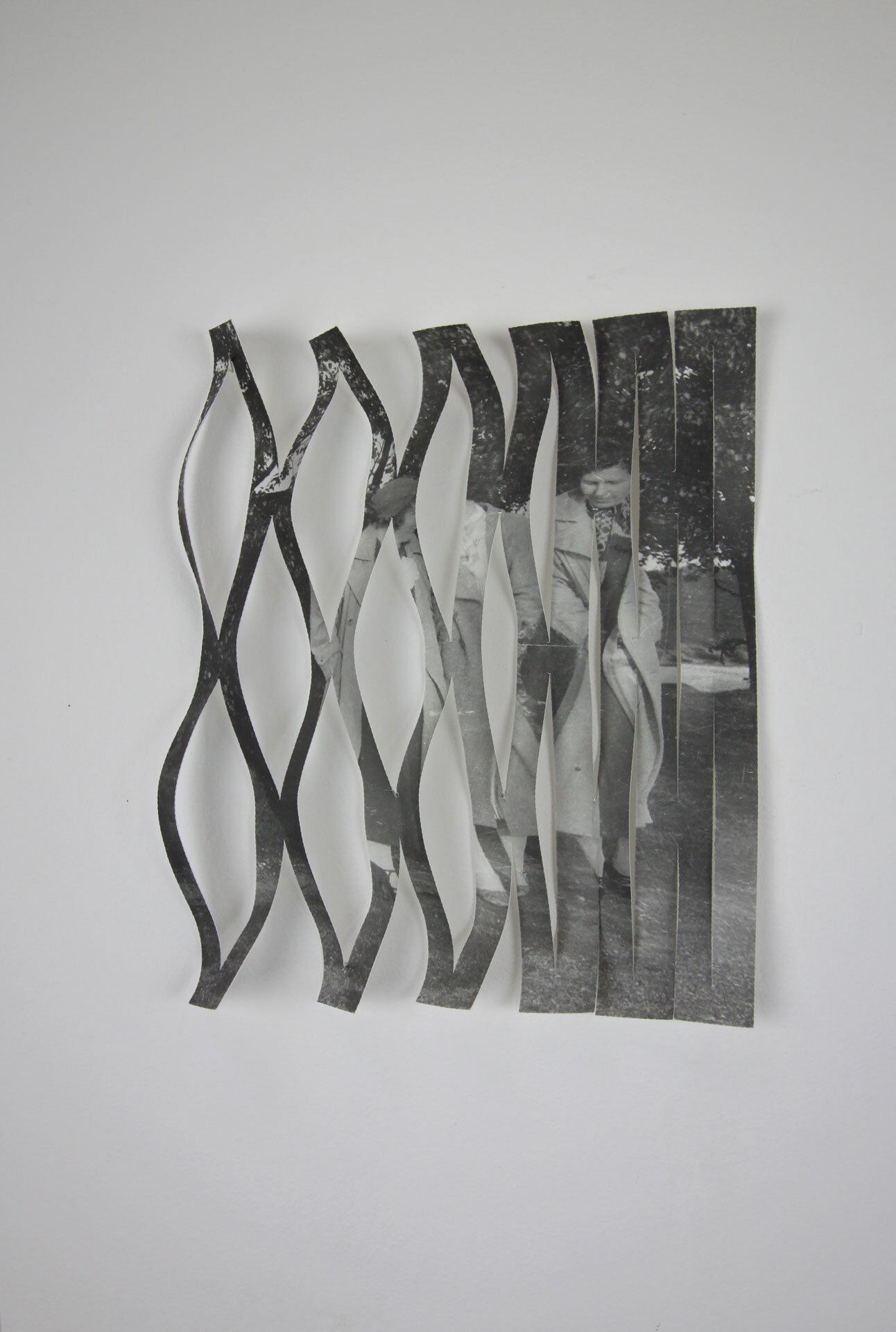

Moving further down the gallery walls, there appears another experimental approach where the photograph becomes sculptural, playing with perspective. We’re met with black and white photographs, cut with pieces bending concave and convex, forming a wave form similar to that in the cyanotypes previously mentioned. We are prompted to move about the piece to find the right perspective, to see the whole image, and even at the “right angle” we’re left confused, scrambling to piece together what this was or could be. Although, since the work draws from found imagery, that feeling may always be there. The feeling of trying to piece together, trying to understand remnants we’ve discovered but ultimately don’t belong to us. Here, Choi invites us to step into this collection of imagery to piece together whatever we may find. This provokes questions in regard to the image itself. The typical four borders of the photograph are challenged here as the pieces become an homage to the fleeting, fluctuating moment captured, where the empty, liminal spaces become just as integral.

Waving Womens, Choi Wong

Now, as the show has shifted from blue to black and white imagery, we see blue emerging again, this time in the form of thread that is infused into a forest. The thread dances among the trees, mimicking their slender nature and gentle curves. We see the manipulated work framed next to the original photograph, bare, subtly hanging from the wall by a set of pins. This curious contrast exhibits humility. We can feel the sense that Choi isn’t simply trying to alter the original, more so honoring it and offering the viewer an alternative perspective: seeing the world with new eyes as the threads of time frolic about.

Blue Landscape, Choi Wong

What’s striking about using thread with the found photographs is the way these founded histories are respectfully woven together. It isn’t so much about leaving a mark, but merely taking these moments into one’s hands and connecting the dots of a memory that is forever in flux.

Speaking of a memory In flux, the gelatine silver print Time - Groupsportrait hints at the ever-changing nature of our memories with its use of double exposure. Here we see a black and white group portrait of women in dresses leaning against a fence in the forest. We clearly see two women but part of the second one to the right becomes distorted. As the image flows to the right, it becomes difficult to distinguish how many bodies there are, it could be four but maybe that doesn’t matter. The image starts to stutter or glitch, quite possibly similar to the way our brains can stutter in the retrieval of the “data” of our minds. The narrative is interesting here as the focus is on the woman most left. It’s almost as if she's looking back through life, and this piece is a mirror into a past self. She remembers that forest and the woman to the right fondly, but everyone else blurs away. What happened here? Was this shot during a family reunion? Did they all just have a picnic? What did these people do before and after the shutter was pressed? Were they genuinely happy to have their photo made? What’s fun about these images is how open they are for interpretation, especially with such a vague title.

There's also a lingering feeling of isolation present in some pieces, especially the multiple exposures due to the narrative focused on one individual. The pattern created by the stutter mimics the wave patterns in the other pieces previously mentioned. These interruptions present a physical isolation that merges its way into a metaphorical one, where the characters become singled out and mirror our psyche through the questions we ask.

Something that comes to mind regarding the original found photos is the idea that someone once discarded these negatives for Choi to eventually find at a flea market. Were they once cherished and printed but someone decided the negatives don't matter anymore? Did someone pass and leave them in a box of old things to be acquired at an estate sale and eventually turned around for profit at a flea market? Are the original prints still somewhere lingering, fading in their frames on someone's wall? Or maybe one day the original prints will make their way to the very same flea market and another artist will acquire them. The questions remain.

Regarding the use of found photographs, there feels to be a sense of community, a togetherness, an urge to see the familiar in others while looking at them. It’s as if we’re peering through a portal, through an hourglass of the past where time, race, class becomes irrelevant. It’s just people. People we could have known. People who maybe remind us or someone we know or used to know. These people act as a mirror. The strength of this work has to do with this familiarity. It evokes a common thread that links to everyday people. We don’t need to be an artist, critic, or historian to feel something looking at Choi’s work, and that alone makes it successful.

Connect with Choi Wong

Connect with Plaatsmaken Gallery

About the Author

Sharyn Bachleda is an interdisciplinary artist based in Knoxville, TN, currently traveling around Europe. She recently completed an art residency at Obras Holland, where she used the darkroom at Plaatsmaken and happened upon this show. She also uses film photography, cyanotypes, and concepts around memory in her work, so writing about Choi Wong's work was a natural endeavor.