Interview with Jullian Young

Interview with Jullian Young

August 2022 Digital Resident

A conversation with Clay, Olivia, & Larkin of Mineral House Media

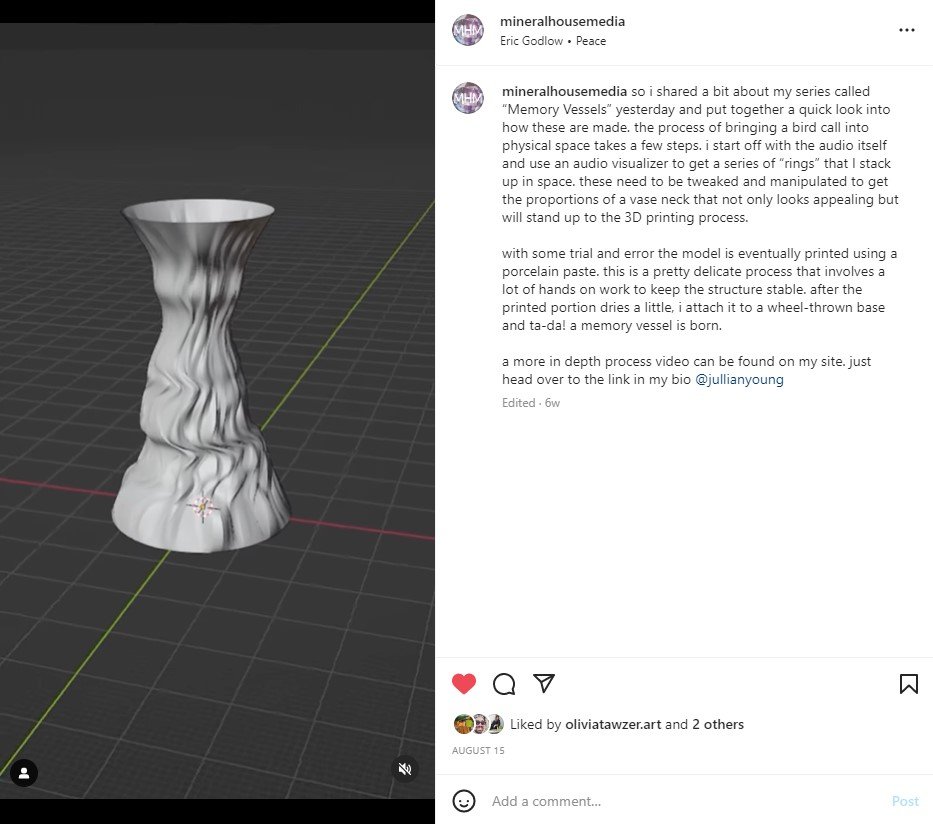

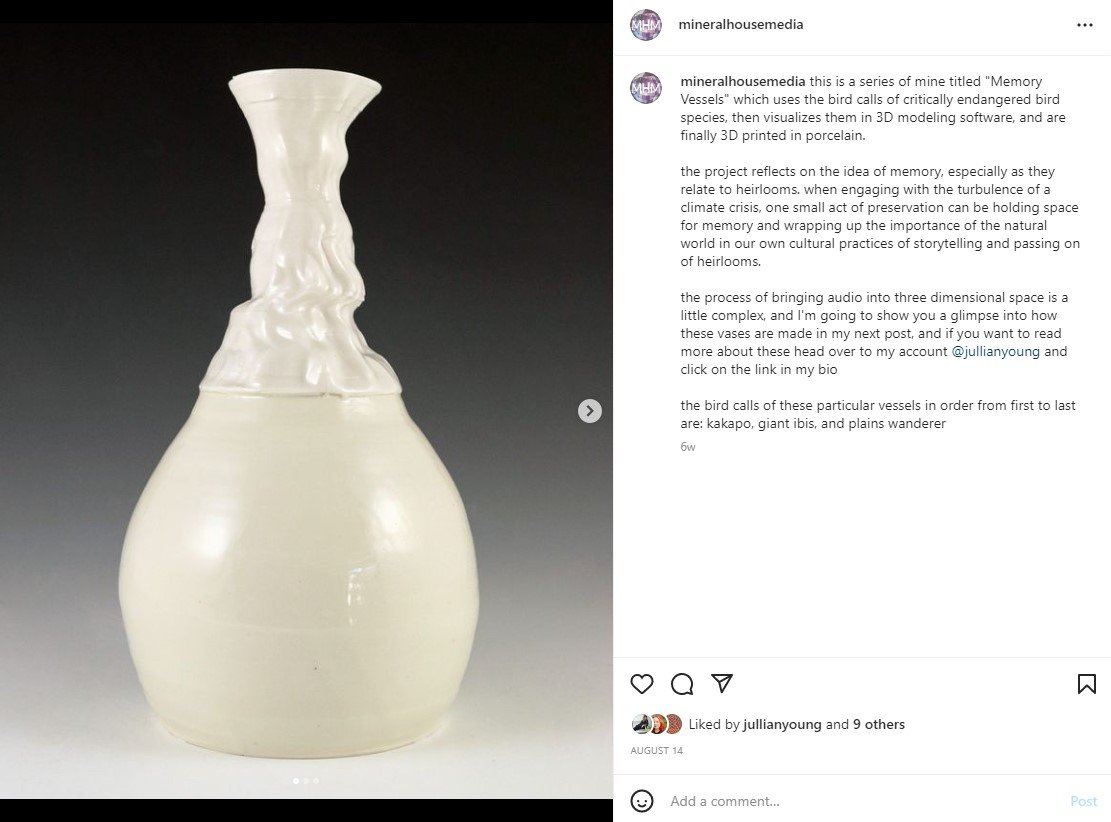

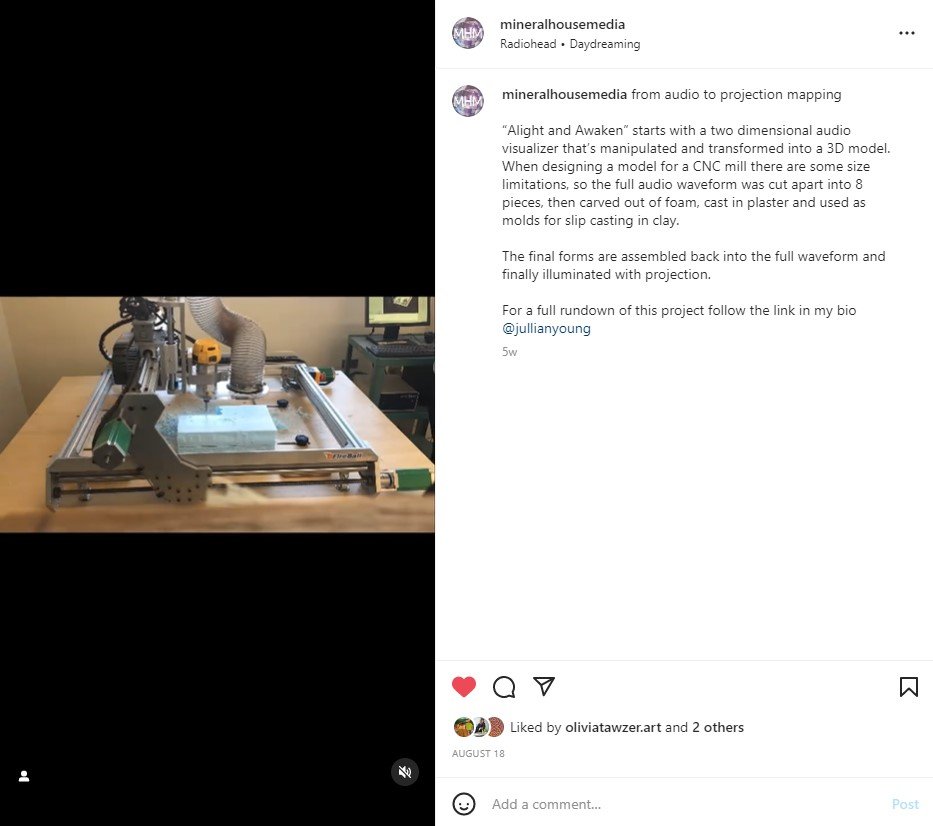

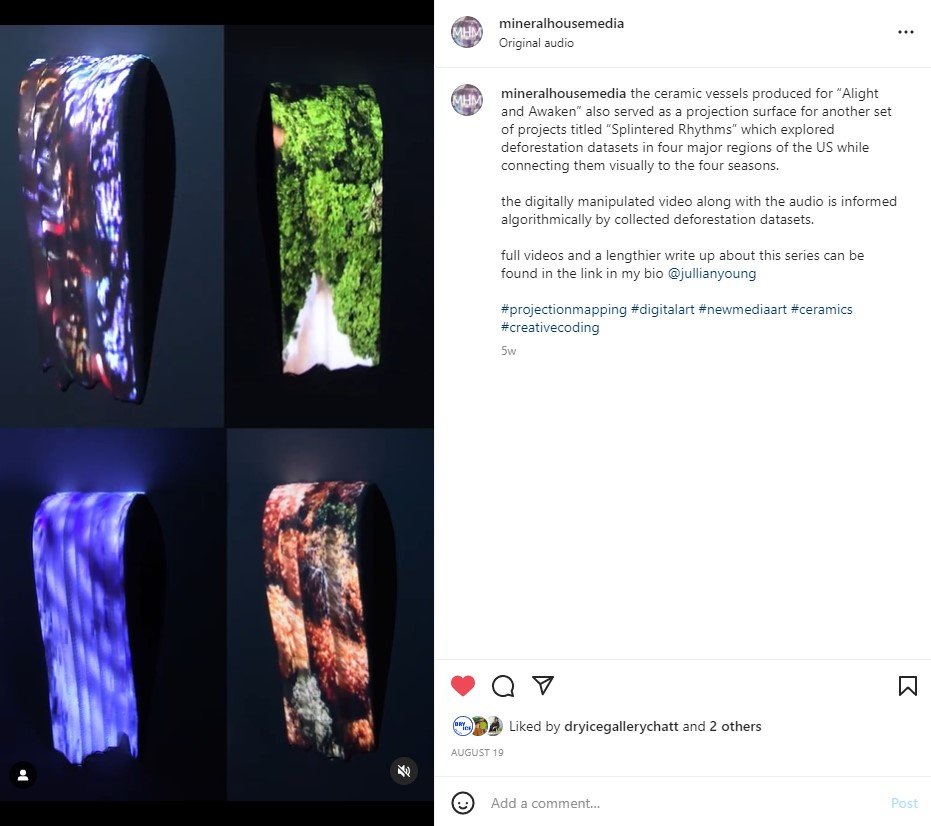

Mineral House Media: The process for making memory vessels is so complex. How did you arrive at the idea and method for making them?

Jullian Young: Really just a lot of play. The Memory Vessels series is one of the first pieces of work to come out of my experiments with 3D printing clay. I was in a graduate school class that explored topics in digital ceramic production and was iterating and exploring (and failing) a lot with these technologies. I think there’s a beauty in being a novice in that you don't have this really structured formulaic way of working with a tool yet.

My first love, in terms of studio art, was wheel-thrown pottery. My undergraduate thesis explored large scale wheel-thrown vessels, and I spent some time after college as a studio potter selling my wares. So when approaching digital techniques in ceramics production, the question really became “what sets this apart from a hand-made form?” and one of the first things I arrived at was computer aided data visualization, and audio visualization.

MHM: Could you talk about the translation of materials in your practice? I’m thinking specifically about the movement between digital and physical spaces, from phenomena to data and back again.

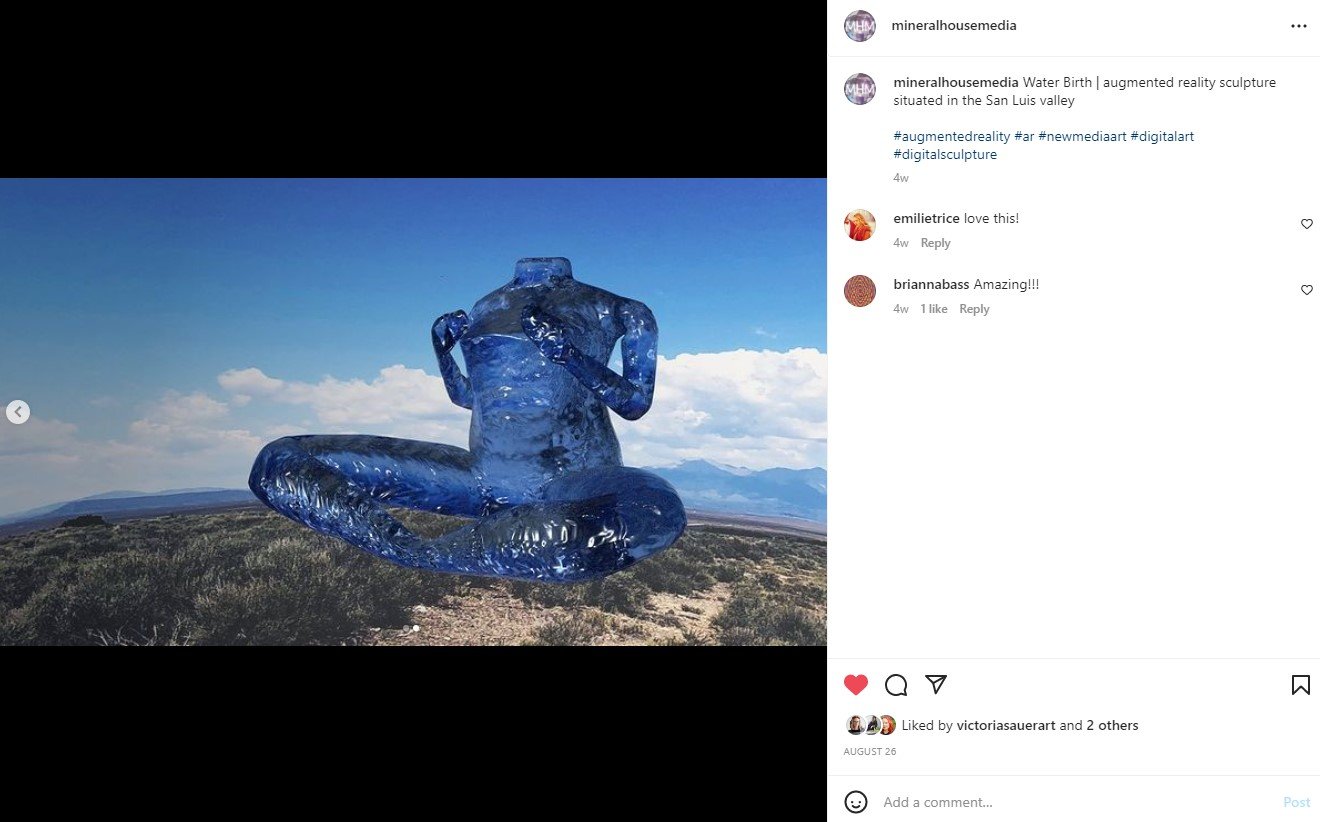

Jullian Young: I have always been someone that loves the tactile nature of things. Physically touching my work, or playing with viewers’ curiosity about the way objects feel is quite central to the way I work. My background is primarily in ceramics, so this immediate feedback of touching my work throughout the process was very present. Shifting into digital or even virtual spaces made this a lot more challenging. But in many ways, I try to create a visual texture that is alluring and makes the fingertips twitch to touch, and something that the digital space offers is that these visual textures can be just about anything. Playing around with texture is one of a few ways I interplay between physical and digital space while maintaining a throughline.

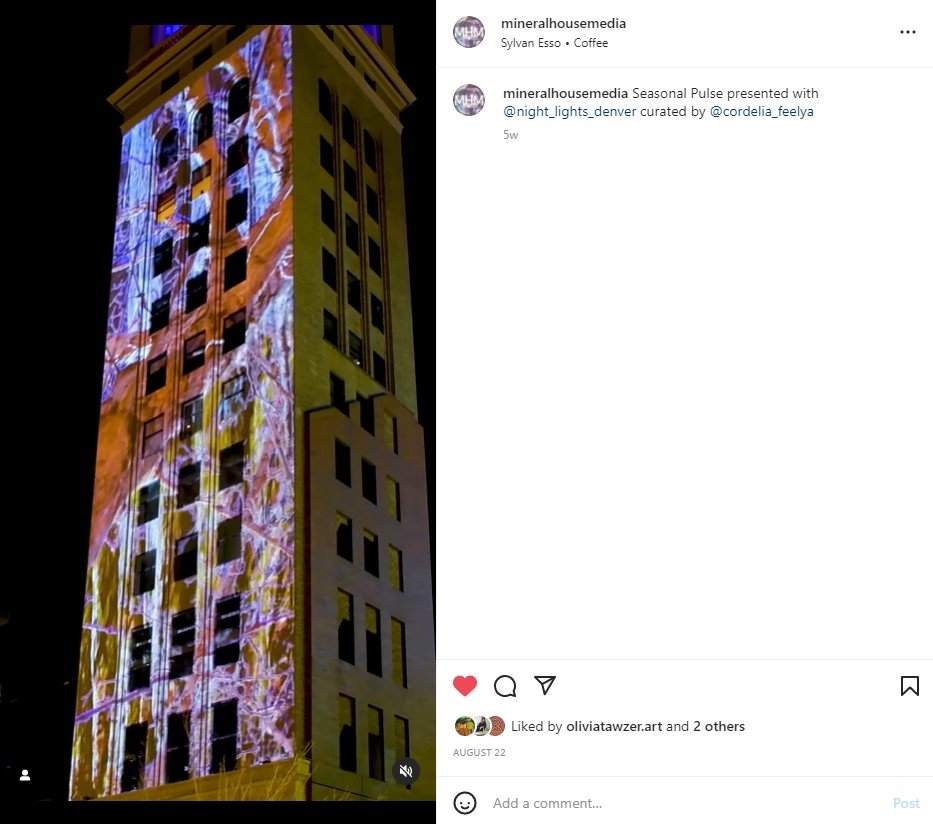

MHM: Curious to know more about your “Broken Home” piece, and the experience of working at such a large, public scale.

Jullian Young: It’s definitely a challenge, but an exciting process once you get to the final product. The first step is just cutting together footage to the specifications of a tower. It’s a very elongated shape (and vertical!), so getting all the visuals to meld and interact on such a long canvas can be tricky. The other big hurdle is that with projection on that scale, quick movements can be dizzying and colors need to be turned up in saturation quite a bit. So as with any creative process there is a lot of testing and retooling. Though, this testing process happens to be projecting video on a building and seeing how it looks, rather than hunching over a piece in your studio.

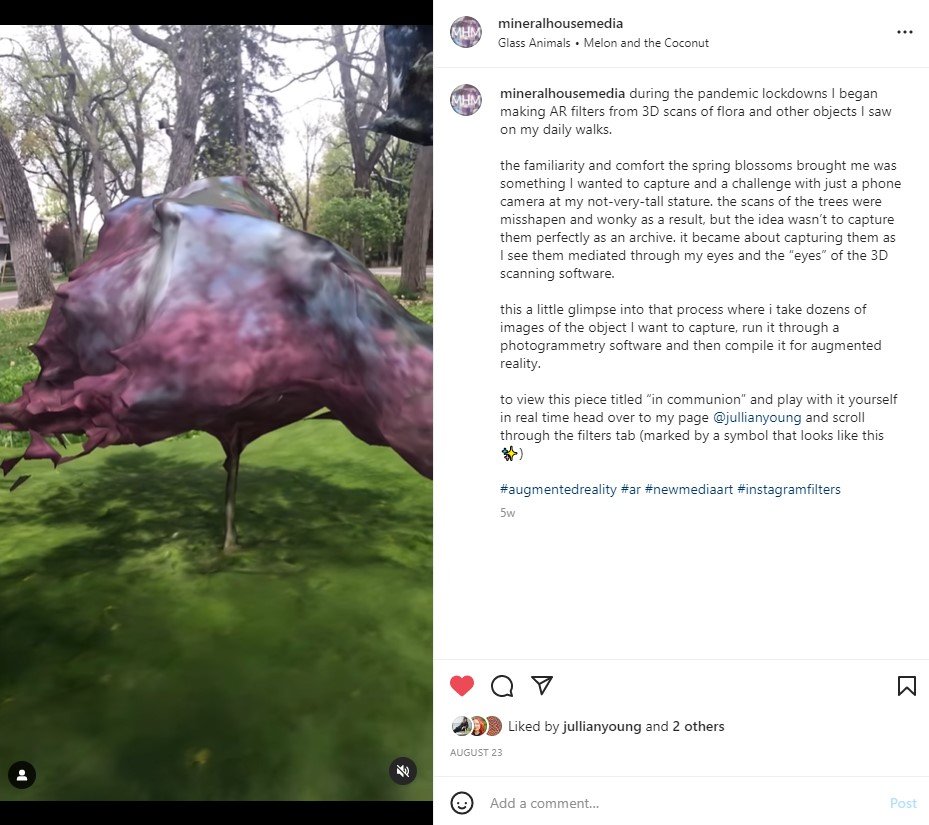

MHM: Can we hear more about your “Communion” series and how the pandemic changed your practice?

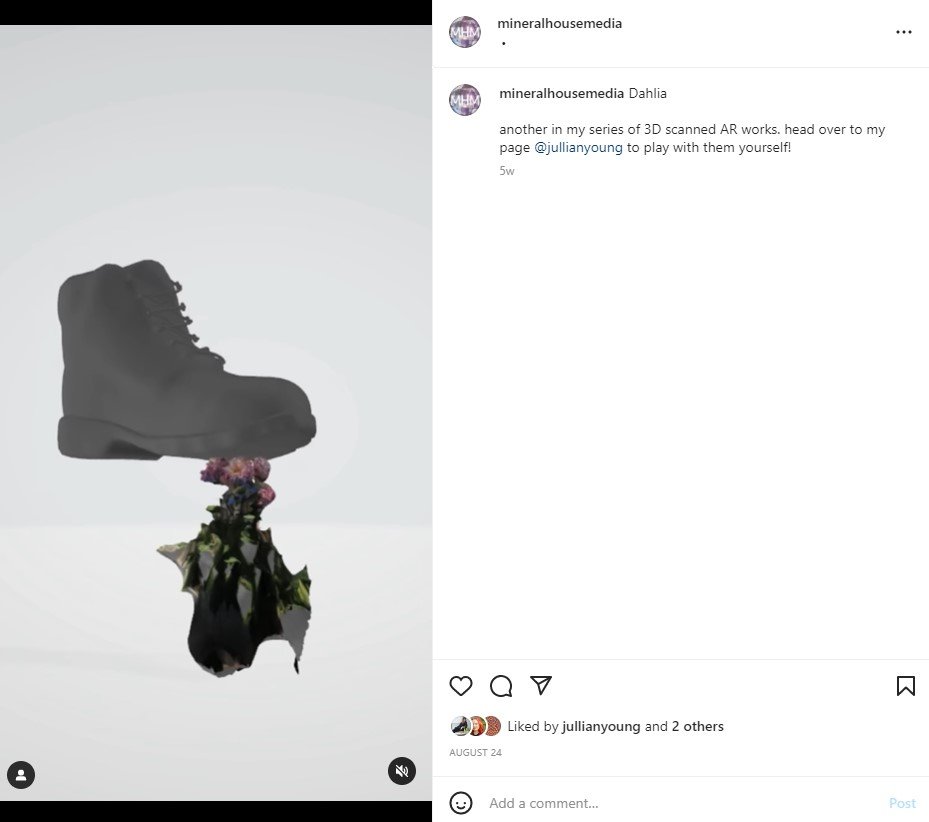

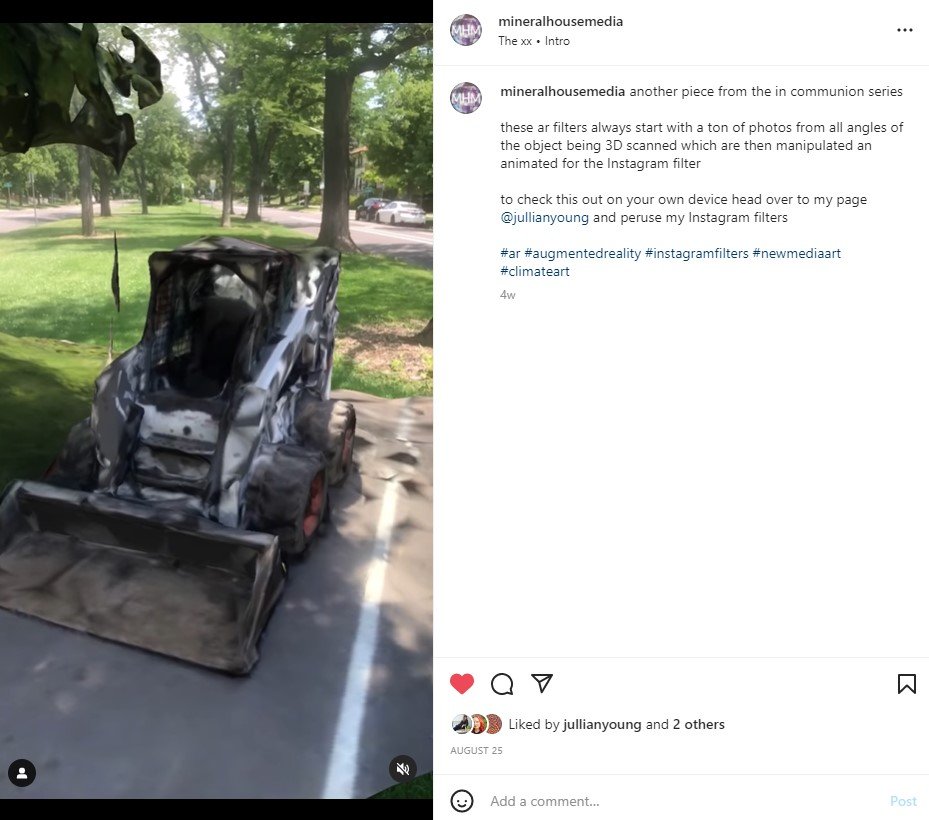

Jullian Young: I think for a lot of artists the pandemic reduced collaborative relationships to zoom meetings, or just removed them entirely. The pandemic lockdowns were isolating in a lot of ways, and artists were not spared in that. As someone who has worked in a university setting for the last several years, the pandemic severed my access to equipment and studio space so for me, art making became about overcoming the hurdle of access. How can I make something with the somewhat basic tools I have at my disposal? And in the absence of gallery shows, how can I make it so that art reaches people in their homes? The solution to that for me really became Augmented Reality.

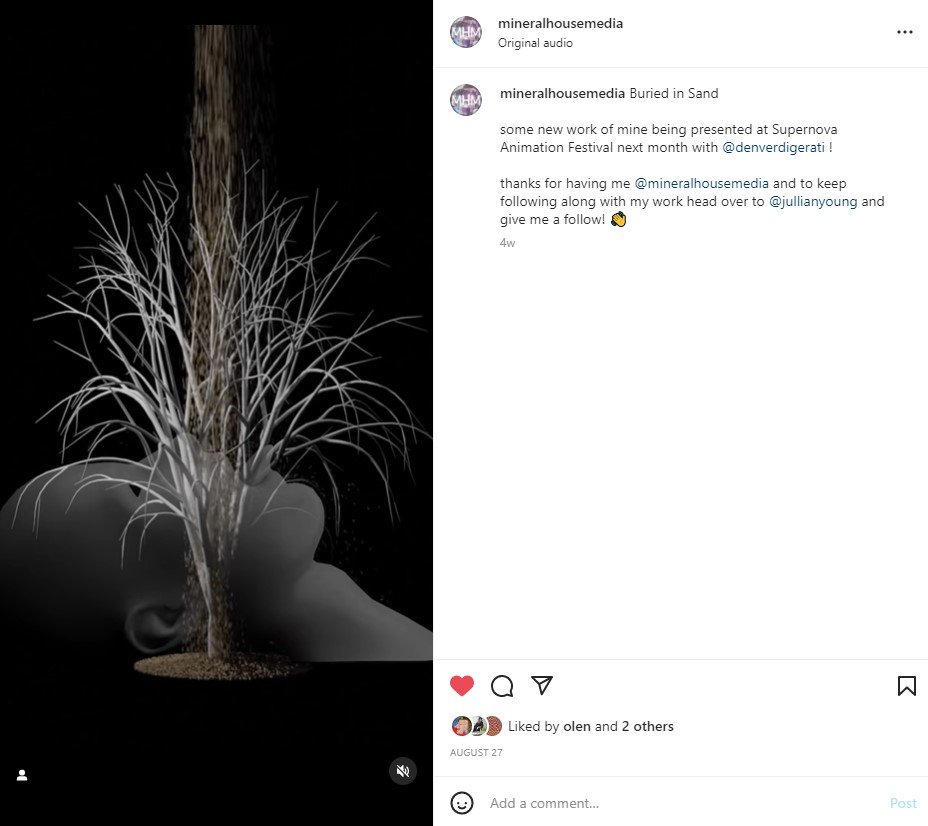

Aside from the sort of structural challenges the pandemic posed, the content within my “In Communion” series was also heavily inspired by the confinement of lockdown. I, like many others, began taking daily walks to get out of my apartment and move around. At that time I became really fixated on identifying the trees in my neighborhood and started taking pictures and notes of the trees I saw along my walk. This transformed into attempting to 3D scan trees and manipulating them in virtual space, and the project sort of unfolded from there.

What became interesting about these scans is that the most comprehensive way to scan trees (or large scale objects) is usually with a drone. I do not have a drone at home, so I resorted to using my phone’s camera. What resulted were these really blobby, wonky, models of trees, but they were models that were directly informed by my own vantage point. Then translating these trees to AR, I was inviting people to see these trees, my trees, through their own lenses, and I think this subtly mimics the sort of alone togetherness that permeated the early months of the pandemic.

MHM: We see a strong consideration for nature in your work. How do you think about your relationship with the natural world? How do you maintain and nurture it?

Jullian Young: I received my bachelor’s degree in psychology and have always had a fascination with the way human beings think and make decisions, especially in their relation with the environment. It was really just a matter of folding that interest into my artistic practice. Part of my process in meditating on new artistic projects is thinking about small, personal, emotional experiences I’ve had and trying to expand it out to see how it resonates with other people besides myself. One such experience I explored for my Master’s Thesis was my relationship with the trees that grew around my childhood home.

There were two large Linden trees surrounded by even more enormous Elm trees around the house where I grew up. I remember playing in piles of their leaves in the autumns, and smelling the fragrant blossoms in the spring. The trees shaped a lot of my idea of “home,” the picture I hold in my head. But throughout my childhood, Dutch Elm Disease started taking out the massive trees in my neighborhood, and eventually in the years before moving out of my parent’s house entirely, our beloved Lindens were stricken with an invasive beetle infestation, which ultimately resulted in the trees’ removal.

My family was quite upset by this, and I certainly grieved over the trees when they were cut down. It was a strange and visceral feeling to be so devastated by something that might seem inconsequential or silly. So with this experience in mind, I set off to understand how my human capacity for empathy is triggered toward non-human entities, and how that could potentially be a tool in guiding human relationships with our immediate surrounding landscapes.

MHM: What does a typical studio day look like for you? Do you work on multiple projects at once, or focus on one thing at a time?

Jullian Young: My studio looks and behaves a lot like what you’d imagine a home office to look and behave like (though probably a great deal messier). I spend a lot of my time behind a computer screen, so it’s not incredibly glamorous or romantic as some might think when picturing an artist studio. But a lot of the fun and experimentation and play exists in this space.

I am someone that has my hands in a bunch of different projects at once, and I find that this allows me to follow my immediate interests in a given day or hour or minute and produces much more sincere and focused work, ironically. I experiment with new ideas and new techniques quite a lot and in working through ideas I test out many different ways to approach the same visual question which can result in a lot of repetition and, frankly, abandoned projects, but also allows me to maintain some enthusiasm for my work without burning out or becoming bored.

MHM: What is your opinion on NFT’s? Are you sick of this question?

Jullian Young: I’m only sick of this question insomuch as I never know how to answer it. I’m quite conflicted about the NFT marketplace, and that marketplace is constantly changing. Still just a bystander in this space trying to feel it out.

MHM: What are the most rewarding and frustrating aspects of your artistic practice?

Jullian Young: Learning new things. Constantly searching for new programs and softwares and tools to work with is the most frustrating, time-consuming, engaging, beautiful, amazing, horrible thing about working in new media. There can be a lot of pressure to keep up with every trend that emerges (and I am always reminding myself that I don’t have to do that). But on the other side of this, it means there is constantly something to experiment with and this creates an environment of play within my own process. I don’t often get bored or feel my work has become stagnant with the tools I use because they change and update (and sometimes get phased out) all the time. It is rewarding and frustrating all at the same time.

MHM: What is inspiring you right now? (i.e. books, music, media, other artists, etc.)

Jullian Young: I’ve been reading a lot of speculative fiction and even building some coursework around that. When working with cutting edge technology, consideration for future use and misuse of said technologies comes into play, and so there exists a kind of marriage between new media and speculative fiction/sci-fi. I was introduced to this idea in graduate school and have built it into my explorations surrounding the climate crisis, and it has offered a lot of depth to the way I think about my work.

MHM: What did the path of making art your career look like? Was there any advice you received that stuck with you?

Jullian Young: The path was not straightforward for me at all. I had, and continue to have, a varied interest in different subject matter which made me a very distracted person when it came to so-called “life goals.” But what helped me get to where I am is that I fully embraced my curiosity for everything. I moved to a different city for a job. That was fun, and I met a lot of people in the art community in the process. That led me to renting space in a ceramics studio and making work part time outside of my day job. Then I started giving more serious thought to grad school and started researching programs. Digital art and new media seemed like an area rife for experimentation and curiosity and growth so I followed that trail. In grad school I realized I enjoy being hands-on in a classroom environment and thought “hey maybe teaching is for me.” And here I am, a professor, getting to explore almost on a whim anything that piques my curiosities.

It’s quite scary and uncomfortable to not have a five year plan, or even a two year plan, and I absolutely felt and still feel that discomfort at times. But I think as I’ve grown accustomed to following whatever paths reveal themselves to me, I become less preoccupied with the idea of where I should be right now. And that is liberating and something I try to remind people entering this discipline, especially my students.

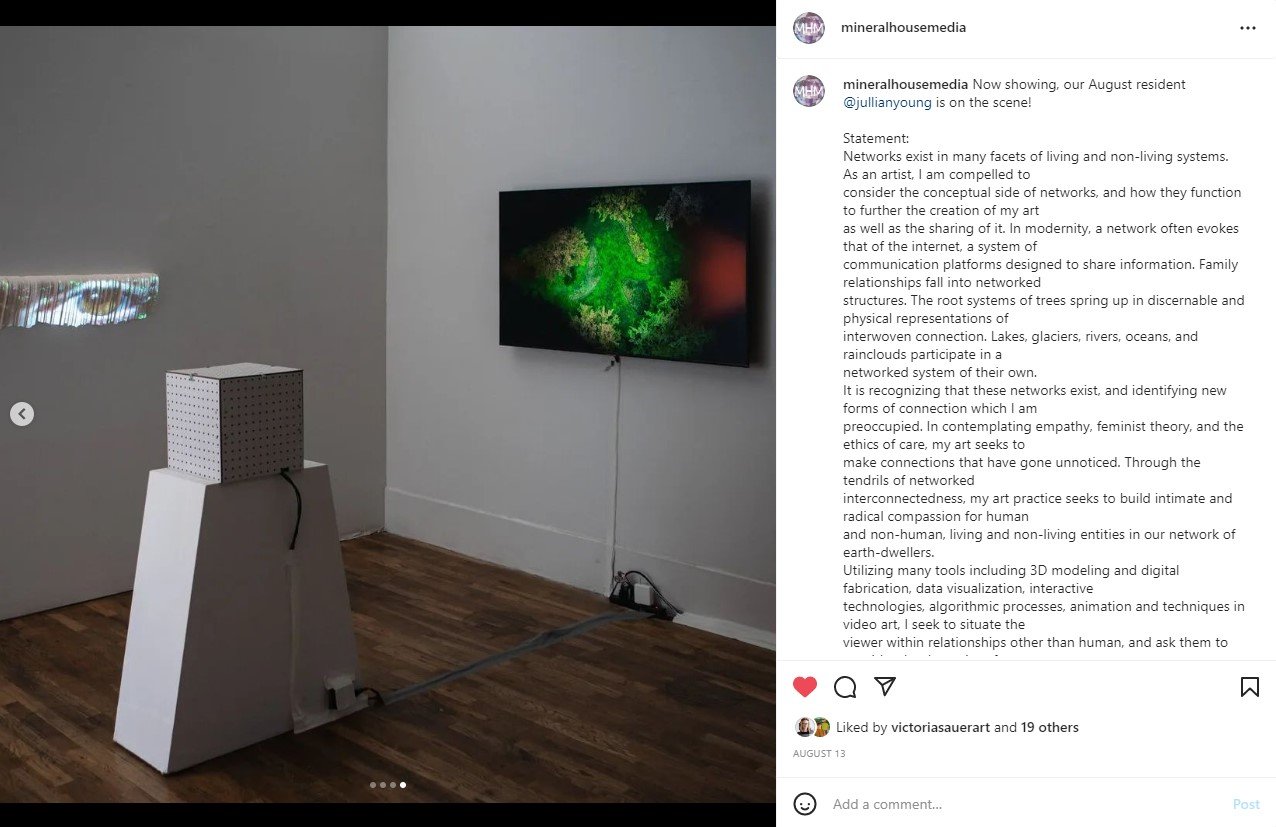

Networks exist in many facets of living and non-living systems. As an artist, I am compelled to

consider the conceptual side of networks, and how they function to further the creation of my art

as well as the sharing of it. In modernity, a network often evokes that of the internet, a system of

communication platforms designed to share information. Family relationships fall into networked

structures. The root systems of trees spring up in discernable and physical representations of

interwoven connection. Lakes, glaciers, rivers, oceans, and rainclouds participate in a

networked system of their own.

It is recognizing that these networks exist, and identifying new forms of connection which I am

preoccupied. In contemplating empathy, feminist theory, and the ethics of care, my art seeks to

make connections that have gone unnoticed. Through the tendrils of networked

interconnectedness, my art practice seeks to build intimate and radical compassion for human

and non-human, living and non-living entities in our network of earth-dwellers.

Utilizing many tools including 3D modeling and digital fabrication, data visualization, interactive

technologies, algorithmic processes, animation and techniques in video art, I seek to situate the

viewer within relationships other than human, and ask them to consider the dynamics of care,

control, and power in an interwoven network that necessitates balance.