Interview with Kate Gordon

Interview with

Kate Gordon

July 2021 Digital Resident

“In a world where reality is a layered event, Kate Gordon’s drawings seek to build illusions that challenge our perception of what is real and what is imagined. For Gordon, the painted picture plane is a three-dimensional installation inlaid with video and, at moments, burgeoning on becoming a pop-up book. The ranging material facts of her work are in keeping with the notion that the dream imagery she mines is itself not rational and does not prescribe purely to naturalistic sensibilities. Her vision is a translation of the utter strangeness of the world.”

-Kate Gordon

Mineral House Media: You talk about collage as a way to freely generate images and keep relationships in flux. Are there any other practices you have that help suspend logic as you produce bodies of images, like free writing or cataloguing dreams?

Kate Gordon: I have a sketchbook that I record my dreams in with little tiny thumbnails. Although, sometimes they wind-up in my Notes App on my iPhone if I am in a hurry. I try not to work from the dreams immediately. I like to let them sit in the book for about six months; that way the most important parts have a moment to rise to a place of importance.

I also like to keep a running list of phrases, mash-ups if you will, going while I work... That way when I am confronted with needing to assign names to finished pieces, for the sake of exhibition or cataloguing, I have some concrete terms to pull from.

Most recent include: Hierarchy of Hot Mess, Playing Dead, Beheading the Sunflower, Snowing Lemons, Batman Jogger, Snake Scarf, Spiritual Emporium.

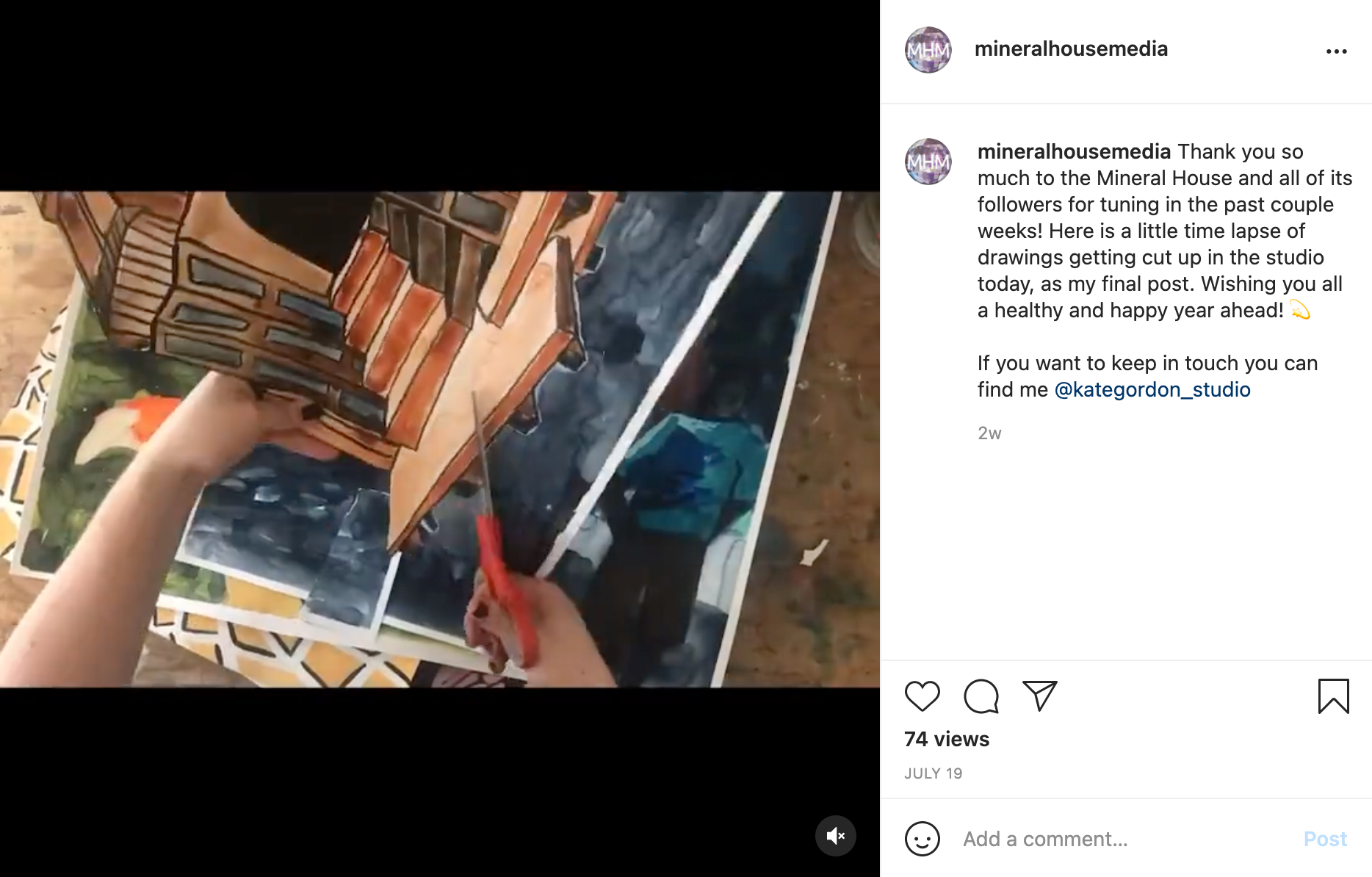

MHM: Can you expand upon the idea of what it means for you to collage from your own drawings as opposed to sourcing collage material elsewhere?

KG: Cutting up my own drawings is a way to keep the process both playful and a bit dangerous. It is a delicate balance between taking decision-making seriously because you have invested your time and psyche into the drawings, while also barreling ahead regardless of the consequences because you trust the process.

MHM: By stitching your collages together, you seem to hold out the state of fluidity for as long as possible. Can you talk more about how you arrived at this solution, and at what point you know the image is ready to become permanently set? Or is ongoing mutability a goal in your work?

KG: This whole process began with one critique in graduate school. I had produced upwards of thirty oil paintings on canvas, they covered every wall in my studio, and they were my first attempts at working from a cerebral space, not an observational one. A visitor to my studio, walked in and looked around and simply stated, “Parts of each of these are working, but none works as a whole, so I suggest you cannibalize them.” Upon his departure, I cut everything up and started rearranging. Adhesive did not make sense for oil on canvas so I began stitching the scraps together. This form of working was generated out of necessity, but has remained ever present in my studio as a way to keep the image space alive as long as possible.

Some work is never truly set, and occasionally “a part” will find it’s home months or years after it’s first iteration. However, most of the work that leaves my studio has reached a level of satisfaction, for me personally, in terms of completion. Unfortunately, I cannot articulate exactly what triggers the end point, all I know is that the feeling of things clicking into place has become more self-evident over the years.

“I was trained with oil and acrylic, but ultimately found my way back to a medium that is often underrepresented in a contemporary context: watercolor.”

MHM: What is it about watercolors that draws you in as opposed to other painting/drawing mediums? Do you ever use gouache too?

KG: I work primarily with tubed watercolor, ink, and gouache.

I was trained with oil and acrylic, but ultimately found my way back to a medium that is often underrepresented in a contemporary context: watercolor. When working with oil or acrylic it is sometimes easy to believe that you are in charge, yet no matter how masterful you become with watercolor there is a margin of “error” and vulnerability that I truly appreciate. Watercolor reminds me to be flexible and completely responsive in the moment to what is happening: to work with gravity, to be sensitive to drying time, and to keep a firm grasp on saturation of pigment versus water. There is a sort of magic that arrives when you are working with the true nature of the medium and not against it… That’s what I am after, and watercolor has proved to be an exciting partner.

MHM: Watercolors often seem to require a bit of planning, but in the process videos you shared during your residency, you seem to move freely and spontaneously. How firm are your ideas of color and form when you begin painting?

KG: I am beginning to understand that there is a natural rhythm to my practice.

For instance, if I have been out of the studio and teaching/living for multiple weeks, I have come to recognize that it will take me some time to reacclimate, and the drawings will be stripped down to lines and greyscale. Once I have had a few days to get into the proper headspace, color will naturally reassert itself. You can tell I have had a very productive studio stretch when the work is at full saturation, with no linear edge for guidance, and very little to no planning.

MHM: Do any kinds of TV shows or movies provide visual inspiration for your immersive environments, spatial backgrounds, video components, etc?

KG: The two most important immersive installation visual experiences to affect the work recently are:

Meow Wolf, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Kunst Kraftwerk, Leipzig, Germany

https://www.kunstkraftwerk-leipzig.com/de

Both places upended my expectations in terms of how my body related to space and a fabricated or painted world. When safe travel is once again possible, I would highly recommend these two projects as a source of otherworldly excitement.

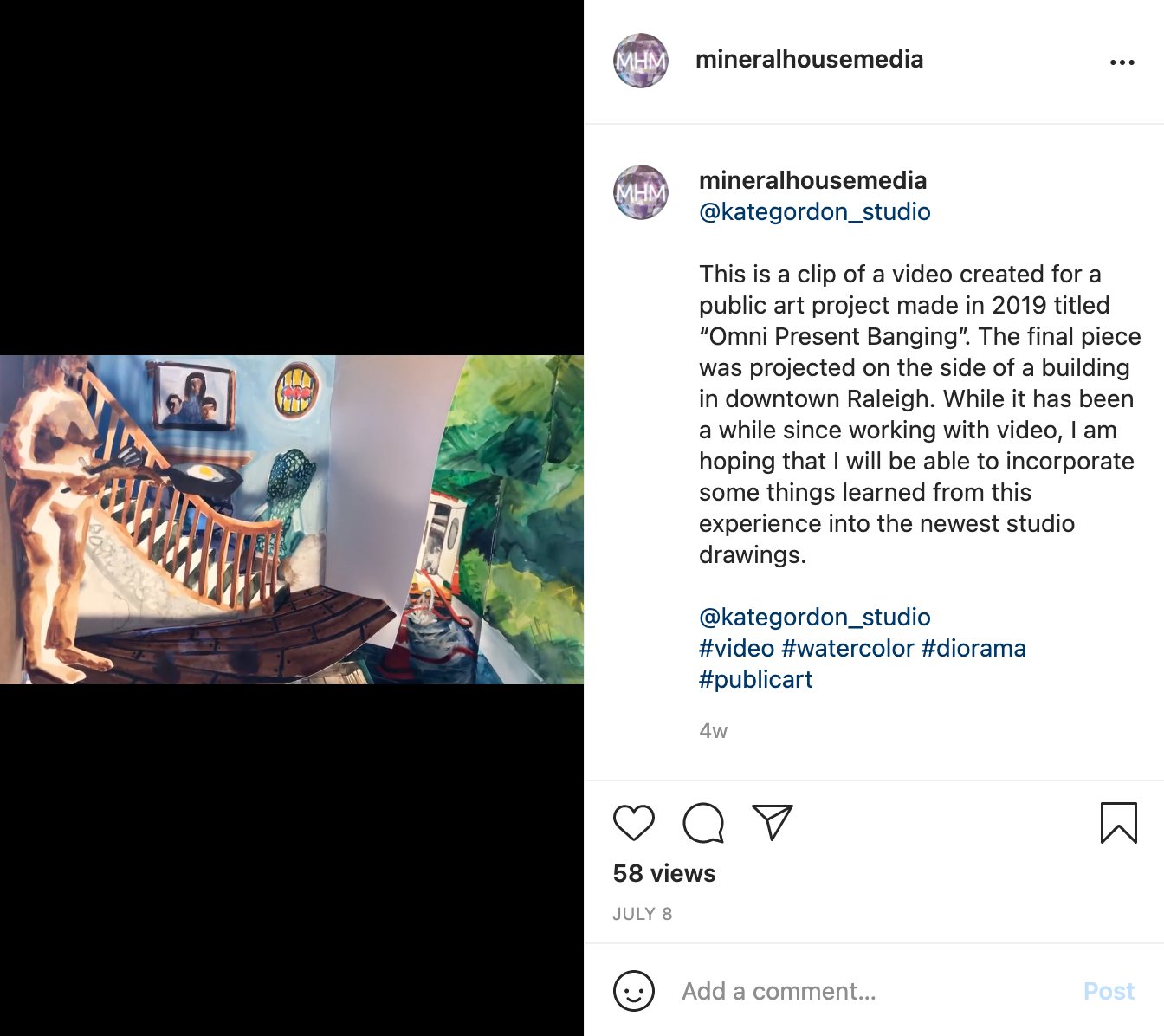

MHM: How does temporality factor into your thinking about space and perception? How do you hope that working with film, a medium entwined with time, will influence your approach to painting?

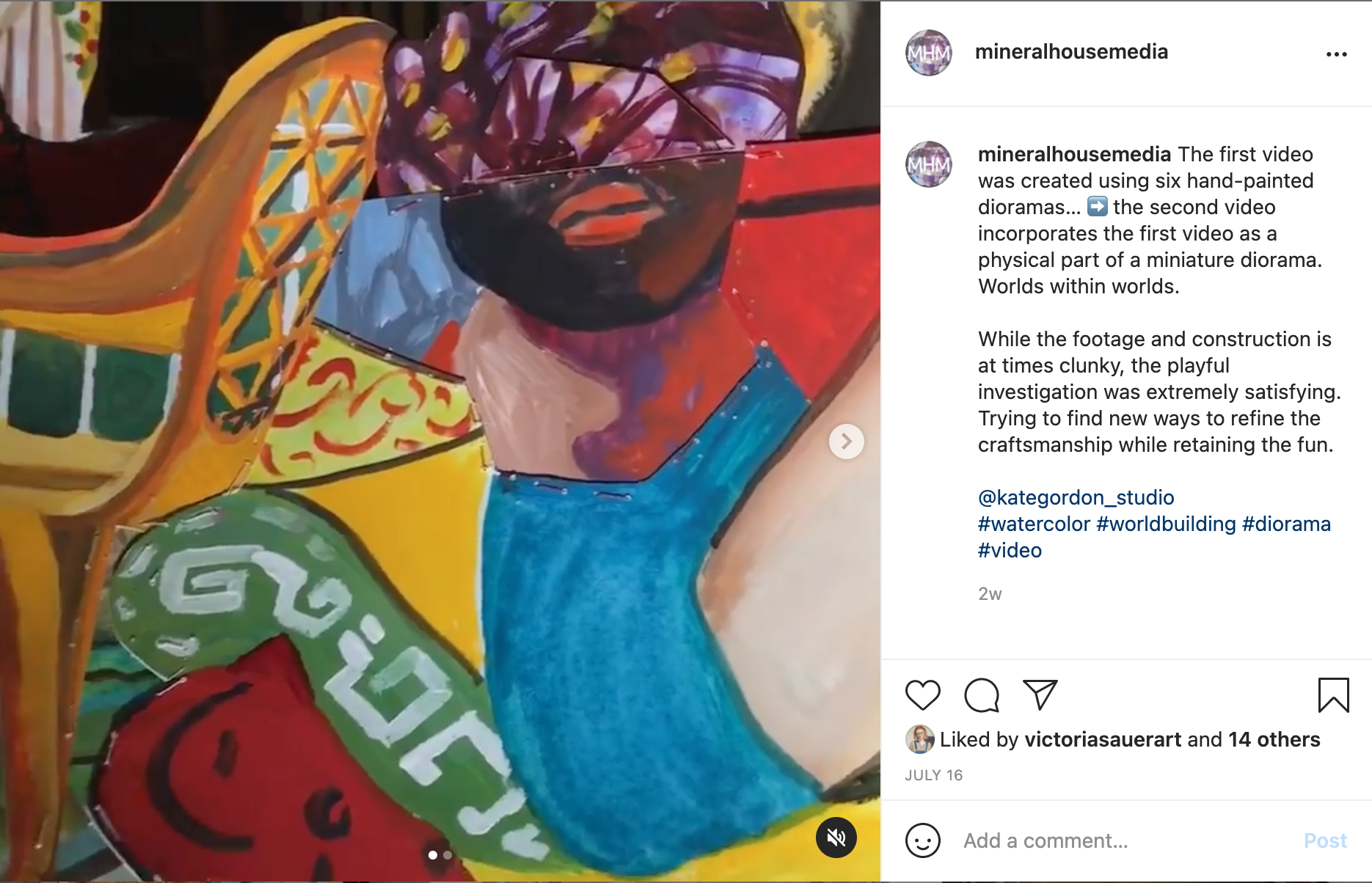

KG: When working with subject matter that is fluid, it feels like a natural extension to engage with temporality as it relates to both painting and film. Some images aren't meant to be fixed to one location on the page. I will admit that I have very little training in terms of film or animation, and that most of what arrives naturally is not well manicured. However, I try to prioritize the strongest, most rigorous painting effort and then allow the film aspects to occur later in the process and only if they arise out of necessity to the concept.

MHM: Can you tell us more about how your recent installation at the Hillard Museum was initiated and planned? What has your relationship been with museums in general throughout your life? For example, is there an early memory that sparked your interest in the diorama as an art form?

KG: Benjamin Hickey, Curator at the Hilliard Art Museum, having recently seen a miniature video diorama of mine, reached out and inquired if I would be willing to take on a challenging installation space in the museum that had never been previously used.

The planning stages were two fold: one aspect involved creating a small to-scale maquette of how the installation would fit within the space, and the other aspect involved material testing of different grounds on canvas so that the work could be exposed to the Louisiana heat and humidity. From there, each piece was scaled up to fit an overall space of: 8’ wide, 13’ tall, and 60’ deep. The entire installation was made lying down on my living room floor during the pandemic, just one piece at a time.

I view museums, especially art museums, as places of deep spiritual peace where investigation, preservation, and reflection are paramount. While studying at Pratt I worked as a Conservation Intern at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, this experience was absolutely fundamental in terms of how I relate to both contemporary and historical forms of art.

“The goal at present in my studio practice is . . . to have the painted world expand into three-dimensional-space, and also for it to be embedded with interactive technology-driven components.”

MHM: How comfortable are you with viewers coming into contact with your work in an exhibition space? Are certain parts of your dioramas meant to be interactive and/or walked through and peered into?

KG: I am extremely comfortable with viewers physically engaging with the work in an exhibition space. The goal at present in my studio practice is for the dioramas to become not only life-size, but also for them to be completely accessible from all angles, to have the painted world expand into three-dimensional-space and also for it to be embedded with interactive technology-driven components.

MHM: Can it be emotionally difficult for you to cut your drawings into collage material? Or does it naturally feel like they’re serving their purpose when they are cut up?

KG: No, it is not emotionally difficult at this point, because I believe that everything can be re-fabricated or drawn again. If anything, the ability to cut up my drawings makes the process less precarious and more exciting.

MHM: When does 2D become 3D for you? As a multidisciplinary artist working with 3D installation of 2D drawings, when does the line of dimensionality get crossed? Does that line even exist?

KG: Almost everything starts in a 2D format, but shifting to a 3D state is ultimately a decision that relates to the concept or goals of the piece. I think there is a fabulous space for magic tricks to exist when 2-dimensional space upends or reinforces 3-dimensional space, but those decisions usually come about organically because a drawing is begging to be left open and not fixed into place.

MHM: In your work, you often situate unconstrained dreamlike imagery within spaces, striking a difficult balance between “no-limits” forms and inherently logical systems like perspective. What strategies, like patterning, do you employ to accomplish this?

KG: This is where the fun begins for me: taking the rules of logic and breaking them—occasionally. Patterning, mirrors, and bodies of water all deal with implied space, while linear perspective lives within the confines of a pragmatic building of space. But then there is stacking of space that comes when images overlap, or even with scale shift, which speaks to objects becoming larger as they move towards you. So the joy for me is about setting up a situation that is spatial and readable, but that is also on many levels improbable or unsettling.

MHM: As a born New Yorker, how has your relocation to Louisiana changed your language of painting? In your writing, you reference a shift in color, and the humid heat’s ability to invoke a “fever dream” state of mind.

KG: Initially, I felt as though I was in sensory overload… attempting to recalibrate to the food, music, pace, language, culture, and vegetation. My arrival was only seven months before the start of the pandemic shutdown, which further added to a sense of disorientation. During the shutdown, my artwork and the world I inhabited were cosmically aligned, in that everything felt like a dream state and at some moments a fever dream.

What I have come to appreciate is that New Yorkers and Cajuns have a lot of similarities. For instance, both believe in hard work and pride of place. In essence, both peoples believe in survival, and the beautiful MacGyver-esque manifestations that grow out of that belief have directly influenced my artwork and my approach to life.

MHM: What are your thoughts on living in your creative space (or creating in your living space), as opposed to keeping a studio away from home?

KG: At the moment, my studio is my living room—a large space with a couch and a couple of drafting tables, yet no television. Over the years my studio space has adapted to the conditions of my location and the availability of resources. I believe that an artist’s relationship to studio space is similar to the goldfish theory—your artwork will grow to the size of the bowl. Some of my most transformational drawings were created in a small bedroom that could only accommodate a drafting table next to the bed.

My dream studio is one that is detached from the house, but on the same property, so that it is readily available, but so that it also allows me to walk away from the work when I am feeling burnt out.

MHM: How can we best stay current with your work?

KG: You can find me on instagram: @kategordon_studio

Or at my website: www.kate-gordon.com

Current shows include:

“Louisiana Contemporary,” Ogden Museum, August 2021-October 2021

“And Now For Something New,” Le Mieux Galleries, July 2021-August 2021

Kate Gordon currently holds the position of Assistant Professor of Figure Drawing & Foundations at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. She earned an M.F.A. from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and a B.F.A. from Pratt Institute. Gordon has shown her paintings, collages and video works nationally; recent exhibitions include a solo show at the Hilliard Art Museum, curation into the Weatherspoon Art Museum’s Art on Paper exhibition, an invitation to create a public video installation at Block 2—a visual platform for new media artists in Raleigh, NC, and a solo exhibition at The Carrack, an artist run project space, in Durham, NC. Past exhibitions include a solo show at 68 Jay Street in Brooklyn, NY and a group exhibition at Five Points Gallery in Connecticut.