Interview with Lindsy Davis

Interview with

Lindsy Davis

March 2022 Digital Resident

A conversation with Clay Aldridge of Mineral House Media

“Nostalgia, experience, perception and memory have a huge role in how the eye filters what the mind perceives as depth. Transferring my concepts from wall paintings to sculptural objects during this time of quarantine in the studio has allowed me to understand object as memory, surface texture as time and shine as the reflection of the self. Having something to hold, something that begs to be touched when anything touched now is thought to be unsafe, taboo. I want to breathe your air again and coexist with something else. With these new sculptures I am attempting to rebuild the feeling of comfort when nothing feels especially comfortable in this chapter in history.”

-Lindsy Davis

Mineral House Media: What does a studio day look like for you? Do you have to travel to a studio space? Do you listen to music or podcasts?

Lindsy Davis: A studio day is usually almost everyday, i'll wake up, make a pot of coffee and go straight to work. Once I get light headed and dizzy I know I need to stop and eat something. By then I'll put real clothes on, brush my teeth and make some sort of food. Then it's usually back into the studio or go into the garden to clear my head and refresh my eyes. I don't enjoy having to travel to get to my studio, I am quite bad at preparing my body for the day before the day begins. For the last twenty years I have had a studio in my living situation, and I don't intend to switch that up.

I listen to both music and podcasts! It is always dependent on my mood and the state of my studio. Sometimes I need to dance it out in the first 20 minutes of the day, sometimes I have to listen to a predictable playlist to get things in order, sometimes it's an intellectual podcast that helps me focus and dive deep into my psyche, or it might be a silly podcast about horrific events. Sometimes I'll even call my close friend up in NY and we'll just chat and talk nonsense which can be nice when you spend a lot of time alone in the studio.

MHM: Can you tell us more about your shift from figurative work to abstraction?

LD: From the ages of about 14 to 21 I was heavily drenched in figurative work. I was exposed to quick gestural figurative drawing at a young age and that energetic response to form got me excited right away. As I delved deeper into the visual metaphors I was creating through objective references to the figure, I started realizing why certain aspects of the figure were so important to me. My signature move was creating morphed concepts of the self you feel you are, all held up on a small dainty foot. These figures were huge, some over 5 ft, all with large abdomens, gaping buttholes, folds of skin enveloping the self, displayed sexual organs in a manner of ritual. At the time, I just lost my father and I was away from home, without therapy. Making mirroring images of the self I felt like was what helped me get through one of the hardest times of my life, up until then.

I was lucky to be plucked by my alma mater (School of the Museum of Fine arts/Tufts) to be a teacher's assistant to three separate courses for a couple semesters. While recruited I spent a lot of time in the drawing studio and relief printmaking studio. So I played a lot. I was starting to get into Richard Serra, at the time I was reading a book of his selected interviews. I mindlessly collaged and printed a mono-print that immediately grabbed me. “Feeling Aloof Next to Serra” was the first work that started my journey into negative space, gestaltism, nostalgia, memory, and identity studies. After I pulled that first print I made about 50 works on canvas to explore what I was starting to see and think about. I wanted to make sure it wasn't a flook, that there was actually something happening in the brain that i was not in complete control over that was putting the pieces of the visual puzzle together for me. Why? How? And over the last twelve years I've been trying to answer those questions. I have done so much research, and continue to do so that helps inform my work and the concepts behind the work. The figure is still in there, just not in an objective format easily consumed by a recognizable limb. The figure is all of us, the brain places us in the spaces we see, so why not play with how the brain contextualizes these spaces.

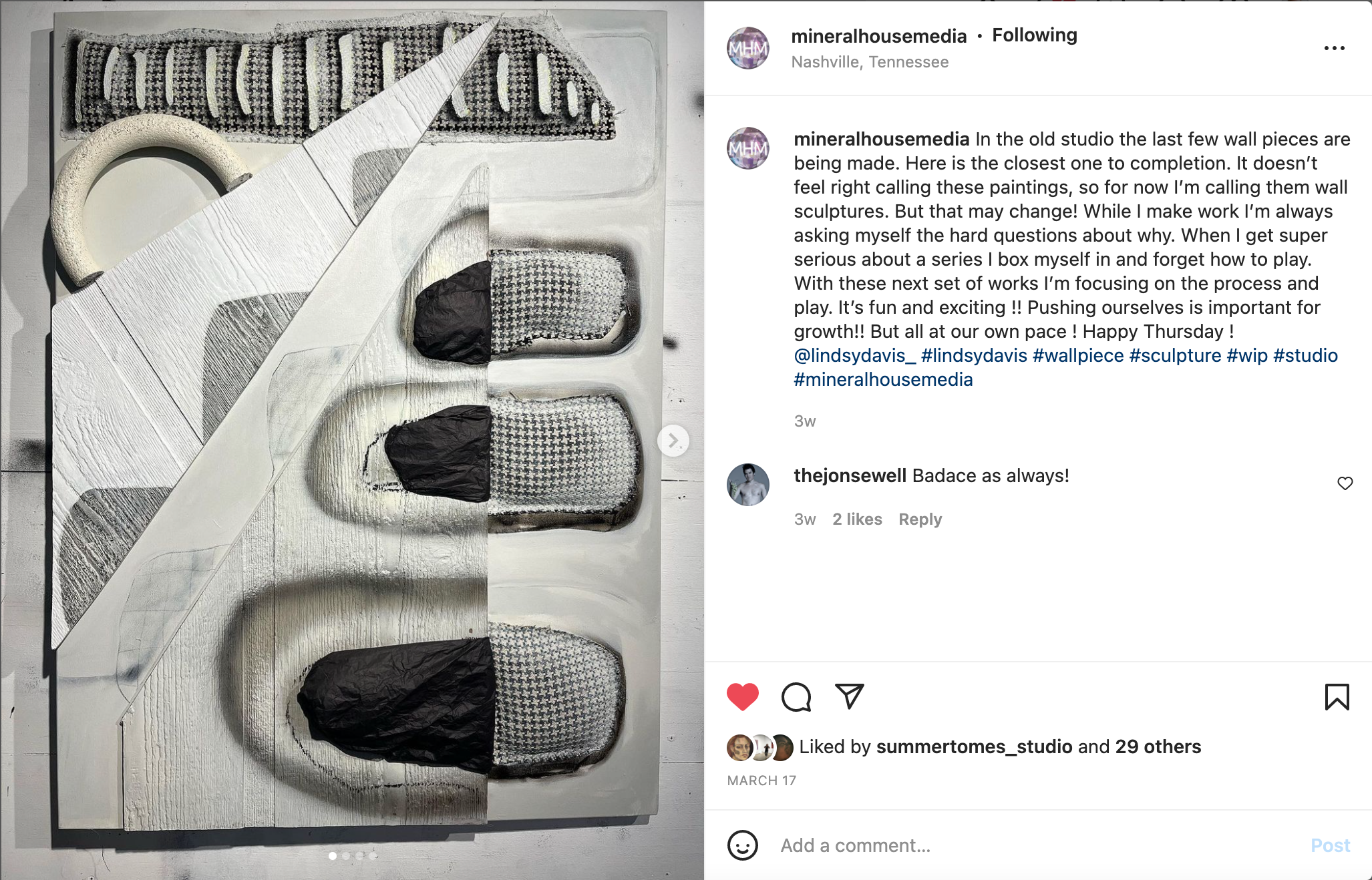

MHM: How do you think about, and use play and experimentation in your process? Do you enjoy losing control of the material?

LD: ALL DAY EVERYDAY BABY!!! Play is huge in my work, letting the material take initial control is god. I burn large branches as my charcoal, creating about 3-5 ft of distance between me and the first markings on the raw canvas. When you burn your own charcoal all the different wood varieties make different marks at different levels of intensity. Vine is different from oak is different from poplar. Then I'll turn the whole painting around and spray paint on the back, letting the subtle bleed through react with the initial charcoal marks. Then from there I'll start reigning it in, slowly.

MHM: Repetition and simple shapes have a regular place in your sculpture. How did you arrive at these motifs?

LD: I find that the most simple shapes and interactions are usually the most overlooked. Simple gestures go unnoticed, whether it be in a shape or in daily routines that become second nature. Over time we don't even see them anymore, even if these shapes, gestures and interactions are the baseline of our objective existence. I'm finding that shining a bit of a conceptual spotlight on these commonplace shapes and gestures rebirths them. Shapes can take so many forms when it comes to meaning. I cannot be sure that you'll have the same connotations with a commonplace shape or gesture as I do. They take different forms, while always staying the same. How many different forms can the same shape take? Trying to play with that is very fun to me. Also it helps to be mindful and thoughtful in your daily interactions—to stop and take notice, it can be a very meditative process for mindfulness.

MHM: How do you source your materials? Some look new, and some reclaimed.

LD: All is reused, reclaimed, given, found, and traded for. Turnip Green Creative Reuse is my second home when it comes to sourcing inspiring material that speaks for itself. Then there is the scrap pile at a few undisclosed locations throughout town I am able to scavenge through. I'll hit up varying lumber yards and reclaimed wood shops to see what offcuts they have and are willing to sell for cheap. My friends also are keen to shoot me a text when they spot something I'd be into. I am pretty resourceful and good at abstract problem solving, so using reused materials really helps with the play of figuring out how these things can work together, visually.

MHM: How did farming for five years affect your creative practice? Did you keep making work during that time?

LD: Farming was a big “skill learn” for me. I collect skills and enjoy being as sustainable as possible. Learning how to grow food was incredibly important to me. I was so lucky to initially start farming for the original hudson valley farmer who pioneered the now bougie organic farm to table restaurants in New York, Guy Jones of Blooming hill Farm. Over time I went to a smaller operation in Beacon NY on “Common Ground Farm.” We were a nonprofit organic farm and we would set up mobile markets in the rapidly gentrifying Beacon, NY. Food accessibility was our goal, and it helped teach me the importance of community, looking out for one another, and sharing skills for future generations.

While farming in Beacon I kept my art practice going. It was slow and it was hard. I set up a 8ft by 8ft stretcher bar square and gridded it out with twine. As my clothes would get holey, dirty, and completely unwearable, I would turn them into the material for weaving into the grid. Between that and playing with painting with soil and dirt and veggie juice, this was a time when I fell in love with meditative processes. When you work outside for 10 hours every single day it is hard to maintain an interactive, challenging, conceptual practice. So I let myself fall into a routine of repetition and small work experiments.

MHM: Could you tell us more about the subtle pink glow in Disassociated Broom 2? Most of your work is bold earth tones, so the touch of color there is eye-catching.

LD: Have you ever seen a male cardinal on a bare branch in winter? Talk about eye catching! I found something mysterious and playful about adorning aspects of works with a zap of color. For “Disassociated Broom 2,” which is a 3D work that is meant to be placed in front of a wall, I wanted to challenge the viewer. 3D works are just that, 3-dimensional, you walk around it, see all aspects of it, but for this work, that was not the case. I wanted to create something that left with the viewer. The subtle pink stands out while the dogmatic urge to walk through an art show prevails. But the eye subtly notices the pink, the glow, where is it coming from? So now, the brain has a problem to solve, is that color really there? These little zaps of unpredictable intrigue is what stifles the brain, makes the viewer stop and try to figure it out. I think of these zaps of color like a cardinal on a branch, you're gazing out the window and boom color, already gone–but it was there- but it flew off. Here I am, still left with its subtle residual glow.

MHM: What is the importance of comfort for you? Do you find it in art, whether in the product or the process?

LD: Life is uncontrollable. You can't know what's going to happen, until it does. The lack of control is manic, crazy, is scary, but it works out, and somehow you're still here, maybe. I like to have a play of both lack of control and full control. My life experiences have made their mark on me where i see the play of control and lack of it, how the pieces fall and we scramble to place them and hope we place them in a way that’ll support the next round, and so on and so on. My studio practice is a micro version of that. I find comfort in problem solving the uncontrollable aspects of material and getting to a visual composition that makes sense from the non-sense.

MHM: Can you tell us more about shifting into the 3rd dimension with your work? What about quarantine pushed you into sculpture?

LD: I started making 3d work when i was a toddler actually. I was put into a “Mommy and me” ceramics class at 2 years old and I ended up staying with ceramics until I was 14. I have a vivid memory of rolling out wet, messy clay and my mother turning to me to ask what I was doing. Obviously I was making a mess, but my first reaction was “Im making a log” which was sufficient for her to let me continue playing and that was it. It was what I said it was because I said it was because I made it, and how could someone argue with that? How powerful it was to learn that I could conduct my own reality by creating myself, when I was a single digit little kid!!

While in school I had access to a welding shop, a woodshop, and the proper instruction if I needed it. That accessibility opened up a whole new realm of potential with 3D work. Welding was my favorite. Once I was out of college and did not have easy access to a welding shop, wood shop, and help if I needed, I stuck with 2d and dived deeper into the abstract psychological concept of gestaltism.

I was playing with small sculptures but not really sharing about it. The tornado and covid made me lose my day job as head printer at a local print shop, so I had a lot of new time on my hands in the studio, which let me draw up new 3D ideas but never fully realize them. It wasn't until I saw Kit Ruethers show at David Lusk in 2020 did that all change. To my absolute luck, Kit was there and able to answer all my questions. Her kindness, and go for it attitude helped inspire me to make my first serious conceptual sculpture “Brutalist Comb”. After that, the flood gates opened and here we are.

MHM: Tell us about the use of Gestaltism and psychology in your work. How does it shape your sculpture?

LD: We can easily boil down Gestaltism to the phrase “the sum is other than its parts” which basically means that each piece of a puzzle has its own life, its own meaning, connotations, associations, but together with the other piece(s) it makes something different. But those associations, connotations, assumptions are always there, informing your decision making and your conclusion drawing. Gestaltism isn't just about the 3d work but how the 3d work interacts with the wall pieces, interacts with the viewer's placement in the space. One does not stand at an art exhibition, one moves through it, so viewing a wall work through a sculpture work, depending on your perspective, will alter that composition. The sum is other than its parts. What you see is one perspective of a puzzle that has many facets, many ways of consumption might change with a twitch of the neck. The thoughtfulness to notice these subtle changes are what is most intriguing to me. Some sculptures have voids which provide windows through it, filling that void with an ever changing space.

MHM: Do you have a favorite psychologist or philosopher that you recommend we research?

LD: Rodrigo Quian Quiroga wrote “The Forgetting Machine” where, without mentioning Gestaltism proper, he uses gestalt imagery in his proven brain science experiments on memory and identity. That was the most rewarding realization, that Gestaltsim is proven. What I initially thought and felt and saw when I first pulled “Feeling Aloof Next to Serra” was correct helped push me further and further into the play of Gestaltism, memory, identity, and nostalgia.

MHM: Who is another artist that you love and recommend we look into? In other words, who is inspiring you right now?

LD: Kit Ruether is my favorite local artist. Vadis Turners new work is extremely interesting and creepy in all the right ways, and Lauren Gregory made a self portrait with fur and painting animations that blew my mind recently too.

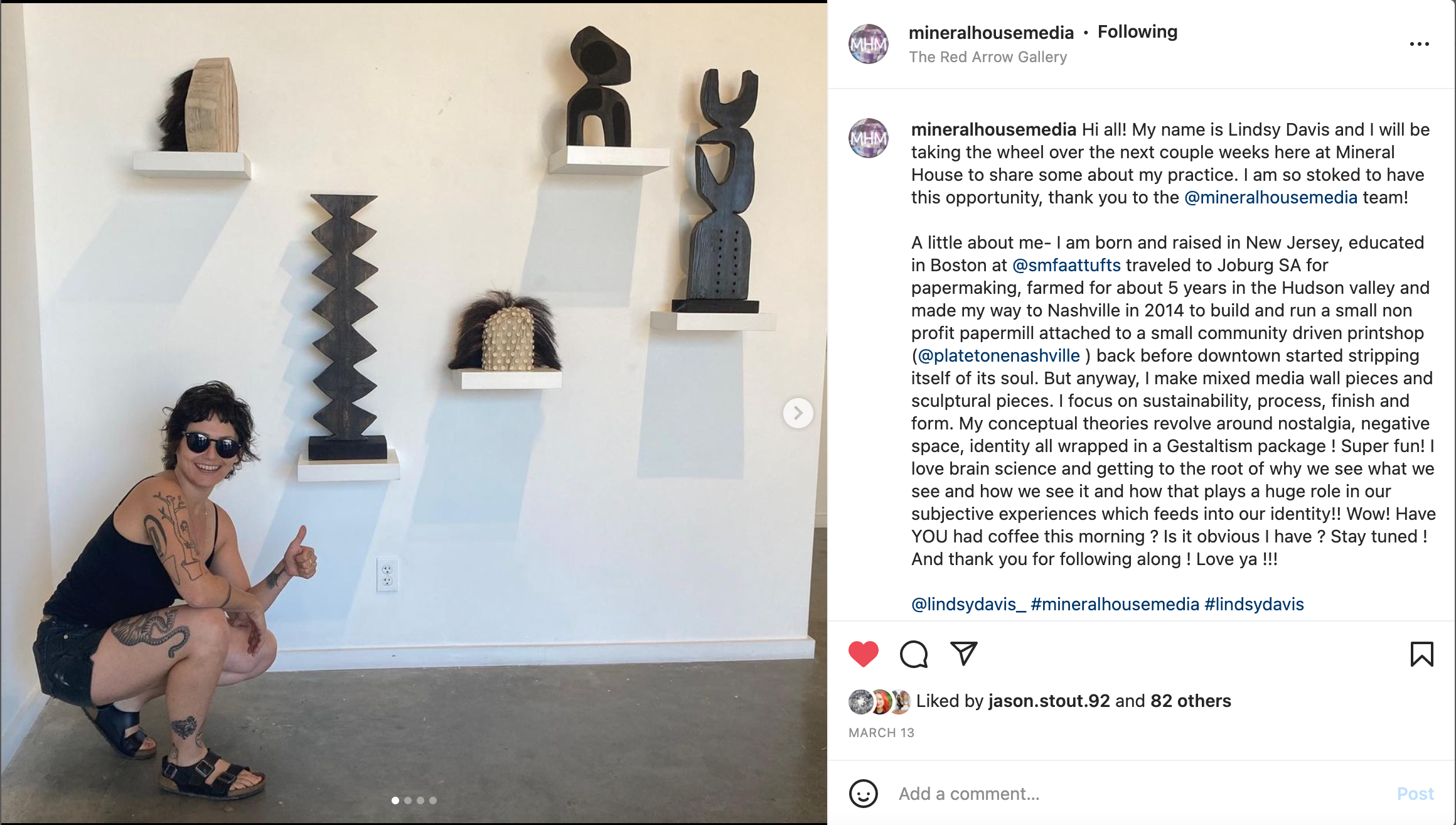

Lindsy Davis is an American artist known for her gesture and negative space work that push and pull the eyes’ perception of space and depth. Lindsy works prolifically in series, her compositions question ideas of perceived perception through Gestaltism. Lindsy has shown internationally, was a National Parks Artist in Residence during their centennial year, she is featured in collections throughout the nation, Canada and South Africa. She has worked with world renowned artists Ibrahim Miranda and William Kentridge. She is a recipient of the National Artist Relief Grant. Lindsy received her Bachelors of Fine Arts degree from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts/ Tufts University in Boston Massachusetts in 2014. She was raised in northern New Jersey, born in 1990, and currently lives, works, and gardens in Nashville, Tennessee. Lindsy is represented by The Red Arrow Gallery in Nashville.