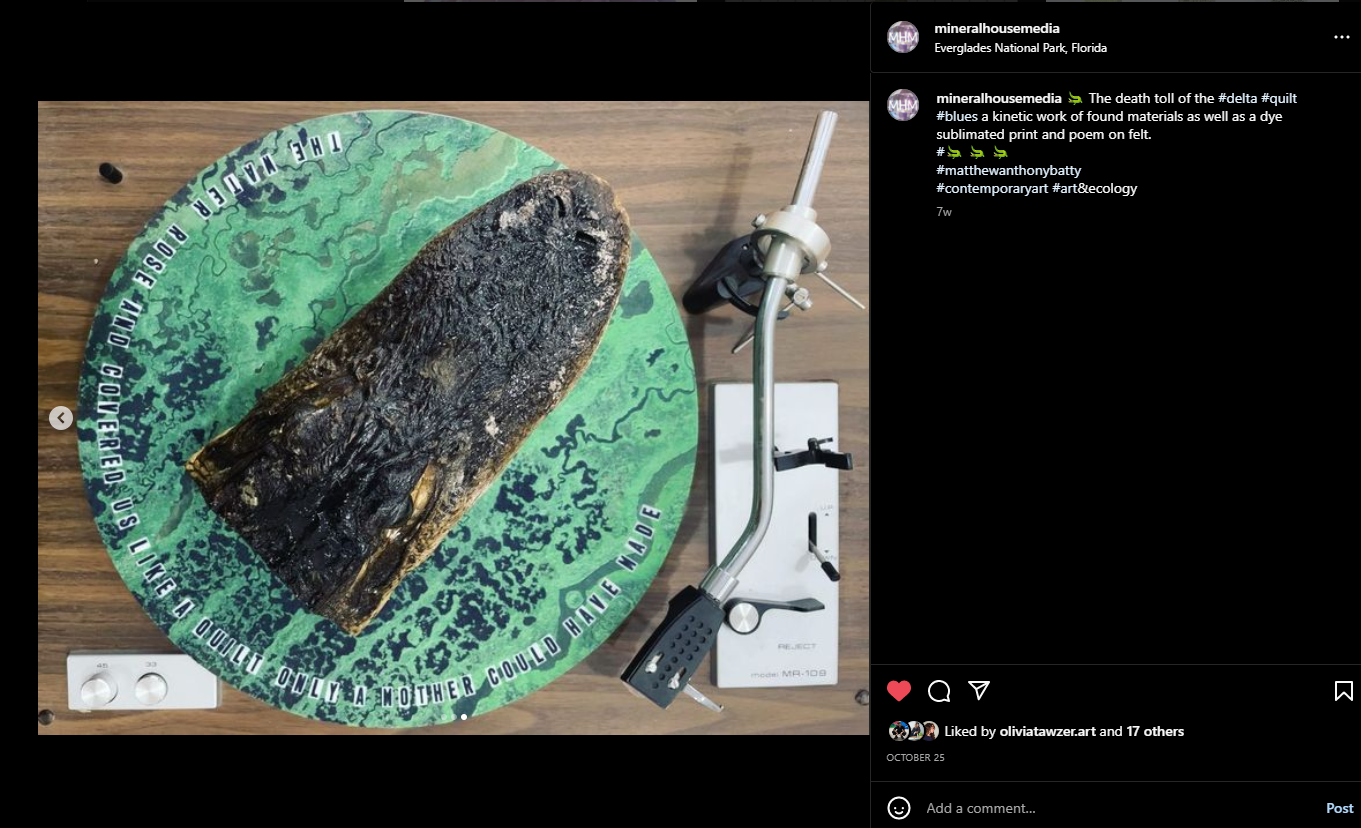

Interview with matthew anthony batty

Interview With matthew anthony batty

October 2022 Digital Resident

A conversation with Clay of Mineral House Media

MHM: The south contains a deep entanglement of artificial and natural materials. What materials from your environment do you find most often influencing, or being included in, your work?

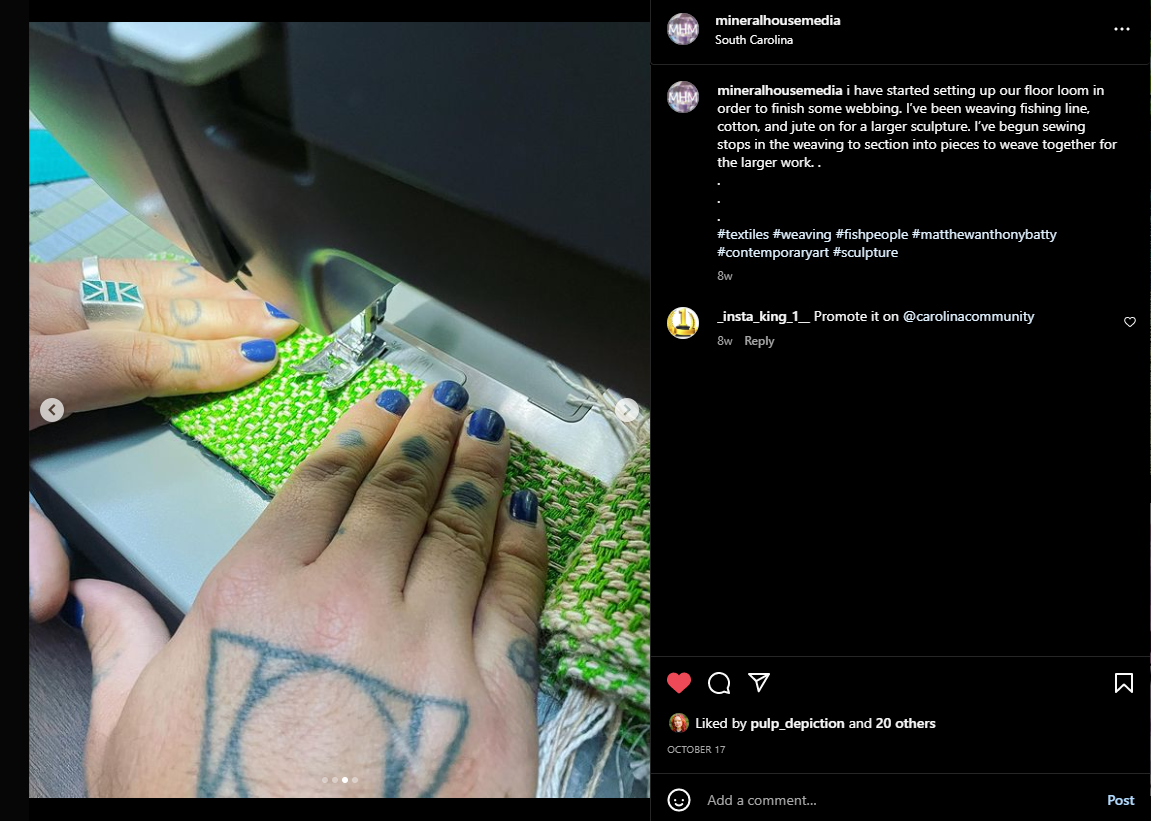

MAB: At this moment in time, I find the materials of entanglement most intriguing when they illustrate allegories to hum_n/nature relationships and are enmeshed with my own lived experiences. When those materials, such as catfish, tackle boxes, coolers, and country music meet that criteria I investigate them deeper, pulling them apart, and putting them back together in some assemblage..

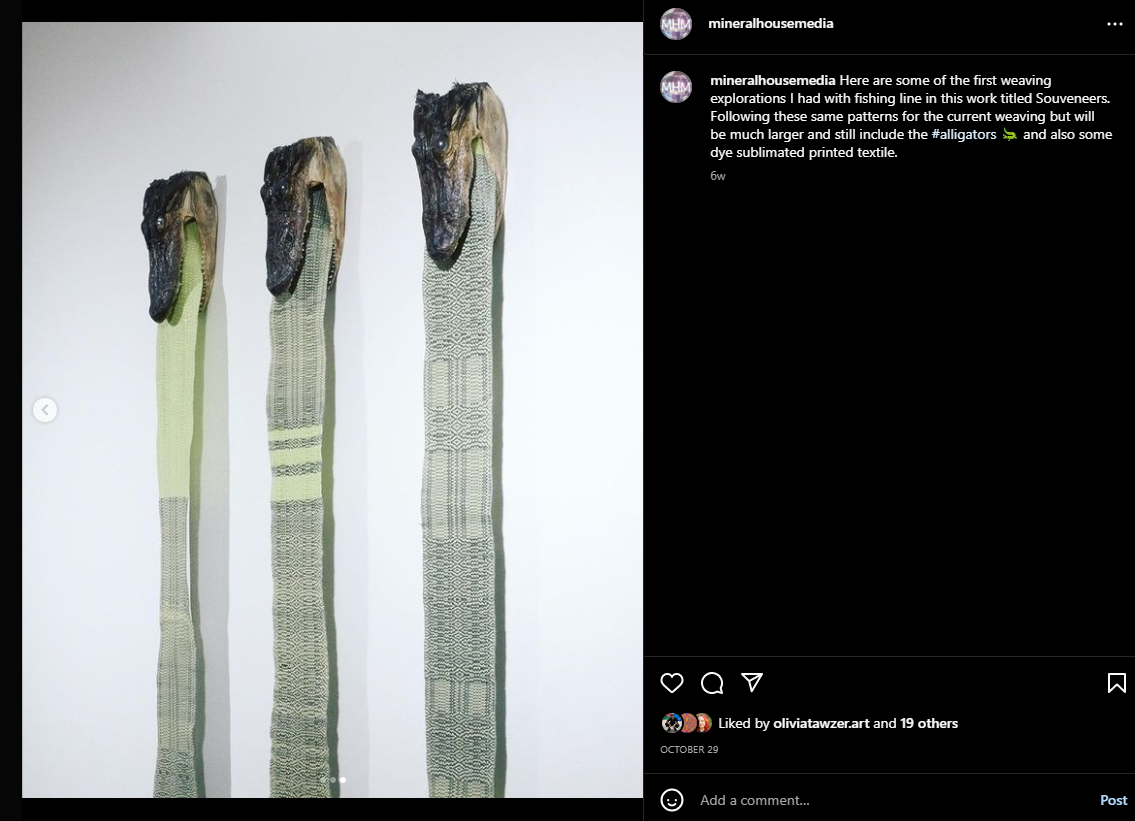

My use of fishing line, both literally and figuratively, weaves together that dichotomy. As a product of American myths of manifest destiny especially from the American Southeast myself, I view the materials with a sense of vitality, and I search to establish a sense of belonging to vs “my belongings.”

MHM: When gathering materials for your work, how do you decide what to take and what to leave alone?

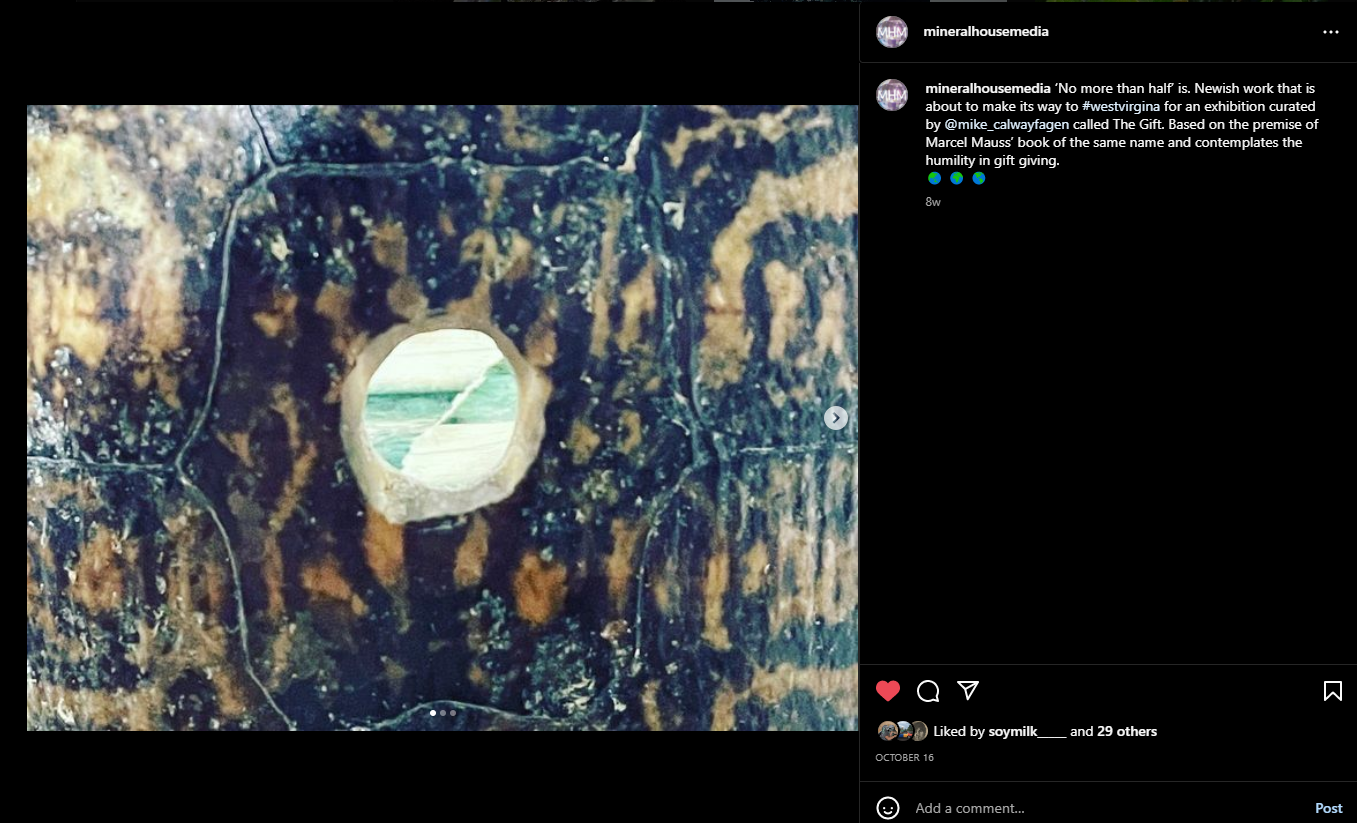

MAB: In the past, I collected a lot more than what I do today. Recently, I have become more mindful of what I take, when, and how. I’ve taken inspiration from a member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation and author, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s words on the honorable harvest and applied them to multiple aspects of my life, but also in my art practice. She writes, “Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them. Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life. Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer. Never take the first. Never take the last. Take only what you need. Take only that which is given.Never take more than half. Leave some for others. Harvest in a way that minimizes harm.Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken. Share. Give thanks for what you have been given.Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken. Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.”

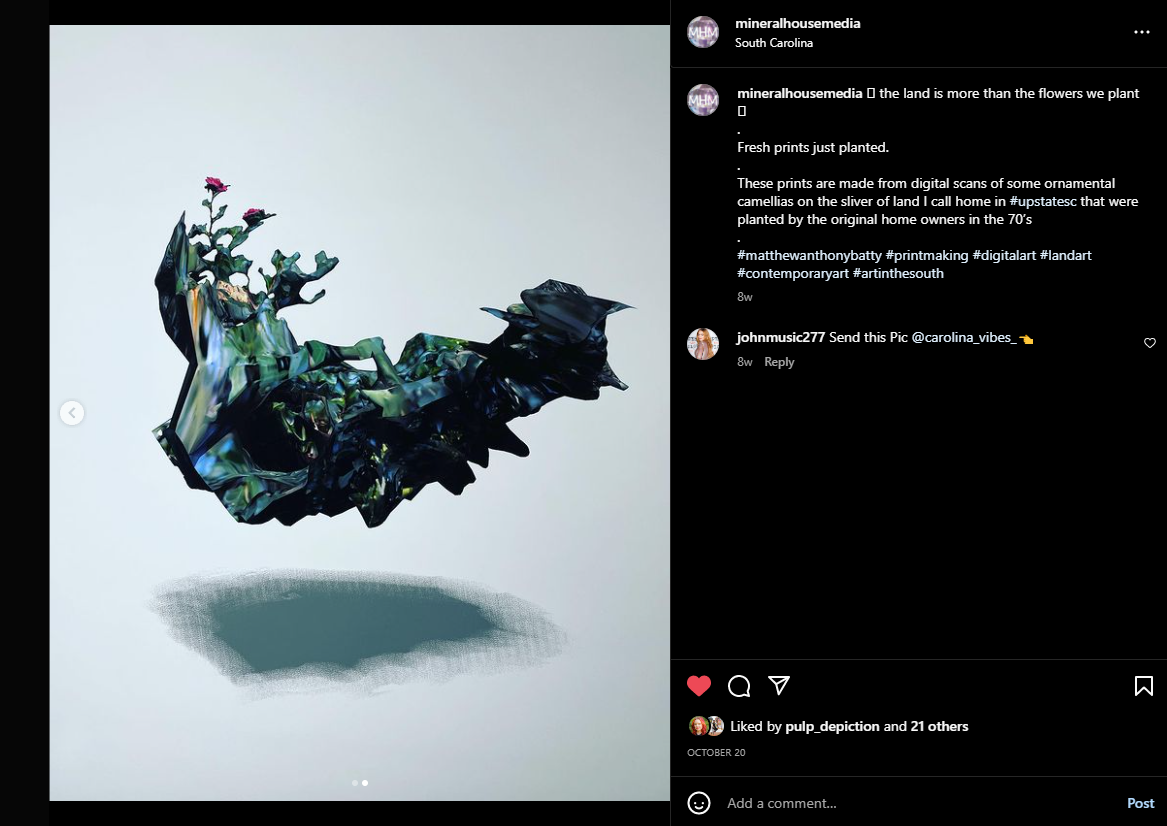

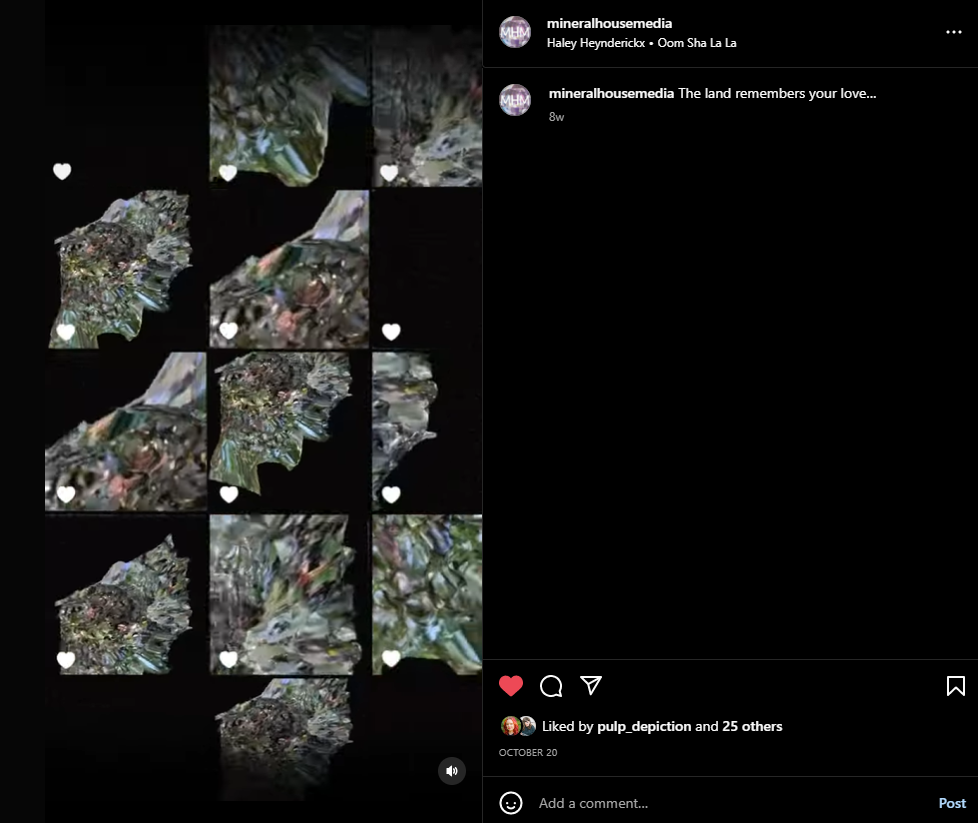

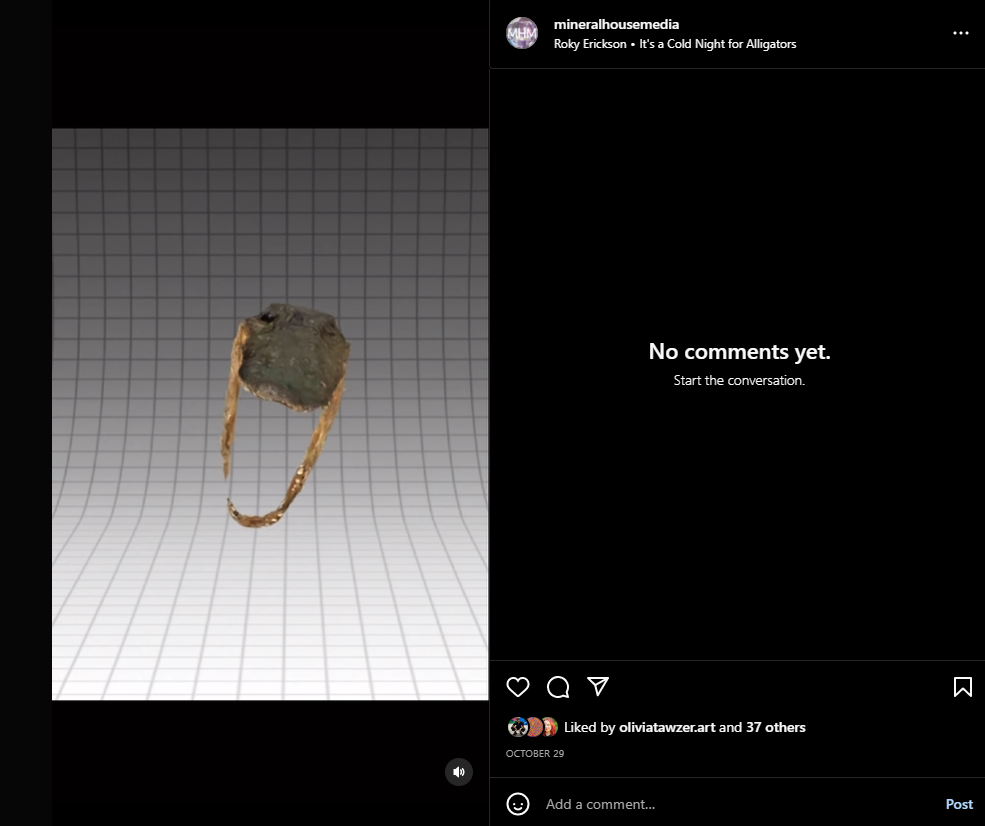

Inspired by these words in Braiding Sweetgrass, I’ve limited how much I physically remove from my environment. In response, I have embraced the use of more technology in my practice such as hiking with photo scanners, using 3-D scanning software, capturing video and photography, as well as audio field recordings with contact mics and hand held audio mixer.

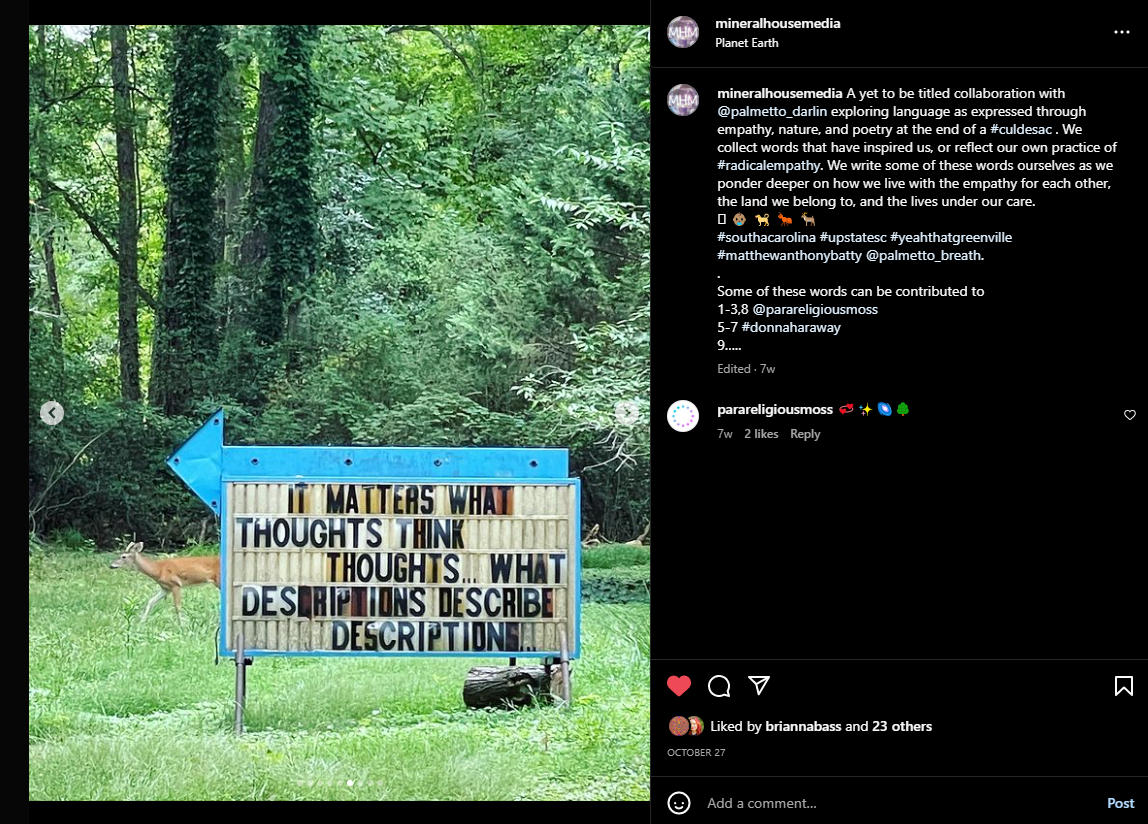

MHM: Where are some places that you have found words for your sign collaboration with Rachel de Cuba?

MAB: My partner, Rachel and I, have been collecting different writings and poems for some time. Sometimes it can be just a moment in something we are reading that inspires us both personally and as it pertains to our art practices. We have included some excerpts from Donna Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble and from a poem we commissioned for our two person exhibition Our Daughter Gathers Seeds from our friend Rose Zinnia. We have also included some of our own writings. Just the other day I changed out the sign with a new poem that was inspired by an observation our toddler made.

We are learning the constraints that we have to put on the written pieces as they pertain to line breakage and character counts. This will hopefully open us up to being able to invite other writers and artists to create text works to be included in this project.

MHM: How does ecology and science inform your practice?

MAB: The ideas surrounding ecology definitely impacts my practice more so than Science. I’ve always been interested in the sciences. However, I am also skeptical of its limitations and its ability to measure abstracts and ephemeralities that make up the ever existing interconnections in a multi-species world. I regularly read books by scientists to build knowledge and find inspiration, especially in those moments of poetic science, where information, facts, and data create an emotive response.

MHM: Where is digital work fitting into your work? How is it shaping your thinking about the natural world, and vice versa?

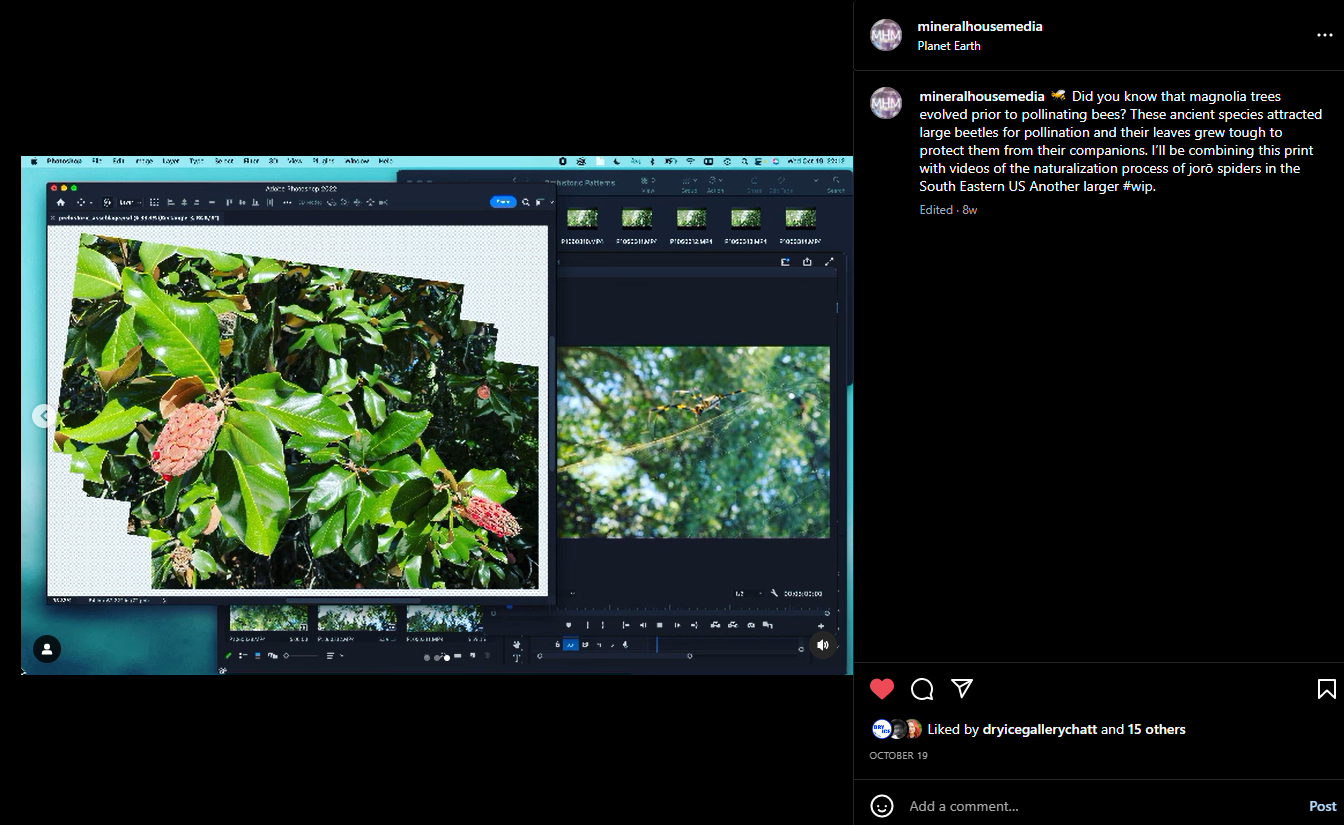

MAB: My embrace of digital technologies in my practice came after I started to frame my ideas about healing hum_ns’ relationship with Nature. It also came after I reconciled notions that Art didn’t always have to include my hand, that it could include the hands of others, hum_n hands and more-than-hum_n hands.

There is a confluence between my inclusion of the digital into my understanding of ecologies. These worlds are as entangled as mycelium with the roots of trees. Accepting that technology was created by hum_ns from an assemblage of different components that were all refined from natural materials can shift our view that the hum_n world as not as separate as we have been led to believe.

My inclusion of digital mediums into my practice felt natural.

MHM: The alligator head is a common sight for southerners. Does it hold personal significance for you? How did it become part of your work?

MAB: Alligators have always been present in my life growing up on the outskirts of New Orleans and later in Florida. Alligators for me hold a place in some of my earliest memories. They have always created this primordial awe and dread. Growing up swimming in waters you couldn’t see further than a foot in front of you. You always had to wonder who was amongst you. For me they are also masters of time. They are resilient. They are patient.

Alligators first became a part of my work in grad school at Indiana University. I had read some accounts of people seeing alligators in the White River around Indianapolis. It prompted me to consider how they got there. Did someone relocate the reptile or was it a seemingly slow migration due to global warming, similar to the armadillos movement north?

It felt like a timely omen, as I was researching the creation of a reservoir that had relocated a farming community and had transformed itself over the decades into a lake with a robust new local ecology. The installation that followed had an overhead video where an alligator swam above representing the one that survives the flooding waters.

MHM: Are you able to pinpoint experiences in your life that pushed you towards artmaking and breaking down the separation of humans and nature?

MAB: It wasn’t really just one experience. It was definitely several moments, conversations, and experiences that unraveled me. It was often questions that were posed to me that lingered, because I didn’t have an immediate response, or if I did it wasn’t sincere enough for me to cast off the question with ease. Lingering on contradictions within myself and becoming ok with that amphibious quality.

MHM: How important is collaboration to you? How have collaborations influenced your thinking?

MAB: Extremely. You can’t have an environment, ecology, world, or whatever term we want to collectively decide to call this existence without it. My art practice is just a mirror towards this sentiment.

MHM: Thinking about your project To Be A Bay. Where else has climate change especially appeared in your research and/or work?

MAB: I feel strongly that all my art is about Global Warming. Is it in your face in order to shock and awe, most definitely not. I approach it with more tenderness, accepting that we are within this hyperobject of Global Warming, and my practice is tethered to it and often to various degrees, but ever present in the research that I build my practice upon.

MHM: Where has water taken you in research/work/life?

MAB: Everywhere. I often think about how from a young age Water has been a cotagonist in my life. I always look for its conference, no matter where I am. Even in a desert it’s lack of presence is meaningful. While I was in the Yukon, in residence with the Weight of Mountains nomadic program, the ice and snow was a way for me to feel at home with Water, but just in a different state.

MHM: You mentioned a practice of radical empathy during your residency. Could you tell us more about what that looks like for you?

MAB: Radical Empathy to me is the practice of empathy with non-hum_n species as well as hum_ns, with animate and in-animate beings. There has been no better teacher than that of my 3 year old child –to see the world through a joyful perspective has been enlightening. It has taught me how to carry that over to mushrooms, camelias, water, joro spiders, magnolias, and even alligators.

MHM: Who is your favorite artist?

MAB: I don’t think I have A favorite. In a historical context, I would have to say Alan Kaprow, Robert Raushcenburg, Ana Mendieta, and John Cage have influenced me greatly. On a daily basis, Rachel de Cuba, their practice and regular dialogue about shared ideas in and out of the studio keep me growing. I’m also regularly inspired by the practices of Dakota Gearhart, Allison Janae Hamilton, Katie Hargrave and Meredith Sellers, Rafa Esparza, Deidrick Brackens, and Cannupa Hanska Luger.

MHM: What are some books, music, podcasts, etc. that are guiding your practice right now? Any that were pivotal for you in the past?

MAB: Currently, I’m reading Sweet in Tooth and Claw by Kristin Ohlson and One Billion Black Anthropocenes Or None by Kathyrn Yusoff, but I regularly return to Rebecca Solnit, bell hooks, Timothy Morton, and Donna Haraway because of their influence on shifting my perspective onto the path I am on.

On the podcast front, I regularly tune into for the wild, Intersectional Environmentalist’s The Joy Report, Hot Take by Amy Westervelt and Mary Annaïse Heglar.

According to my Spotify Wrapped, I listened to a shit ton of Jake Xerexes Fussell this past year – I think I found their music late last year. I’m always inspired by the honky-tonk poetics of the Silver Jews. In my studio I have Blood Orange, Philip Glass, Laurie Anderson, Haley Heynderickx, Adrianne Lenker on my regular playlists.

MHM: Ok, last question. Let’s say you go for a walk right now. What is your favorite color that you see?

MAB: I would have to go with that color of a confluence of two rivers that are carrying different sediments, that push and pull between a murky teal, and a flowing olive.

matthew anthony batty was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, and grew up in and around Florida. their artistic practice is as diverse as the landscapes and ecologies they are inspired by. They are a transdisciplinary artist working across such mediums as video, sculpture, sound, social interventions, and image-making. matthew's work explores themes of dark ecology, the manufactured division of nature and culture through myth making in modern N. America, and environmental justice in the anthropocene/plasticene/capitalcene. Utilizing the muddiness of the in between to create new visions of coexistence and speculative ecologies of naturecultures, matthew’s work explores fragmented moments within the anthropocene, and hyperobjects like global warming in order to offer a way to navigate out and towards what Donna Harraway calls the chthulucene, an epoch where it is acknowledged that hum_n and nonhum_n are inextricably linked.